Sandy Park High Street is one of a number of inner city satellite villages that seem to orbit round the centre of Bristol. Shops, cafes and offices occupy the ground floor of terraces that stagger up a hill. A collage of coursed rubble and pebbledash leads to St Cuthbert’s Church, a massive red brick building which commands its position with polite robustness as it looks back over rooftops, towards the towers and spires of the city beyond.

This is an area that I know well, my parents live around the corner and I spent many intermittent years here as a young adult. Over the past twelve months I have exercised any latent local knowledge to inform our reordering proposals for the aforementioned St Cuthbert’s Church. Working on a building that you know, amongst a community to which you are tied presents a certain tension, or rather a heightened sense of responsibility. I could hear the mantra of previous community design workshops ringing in my ear – “you’re the expert of your area”. Hopefully this went beyond knowing the best place to get a coffee before a client meeting.

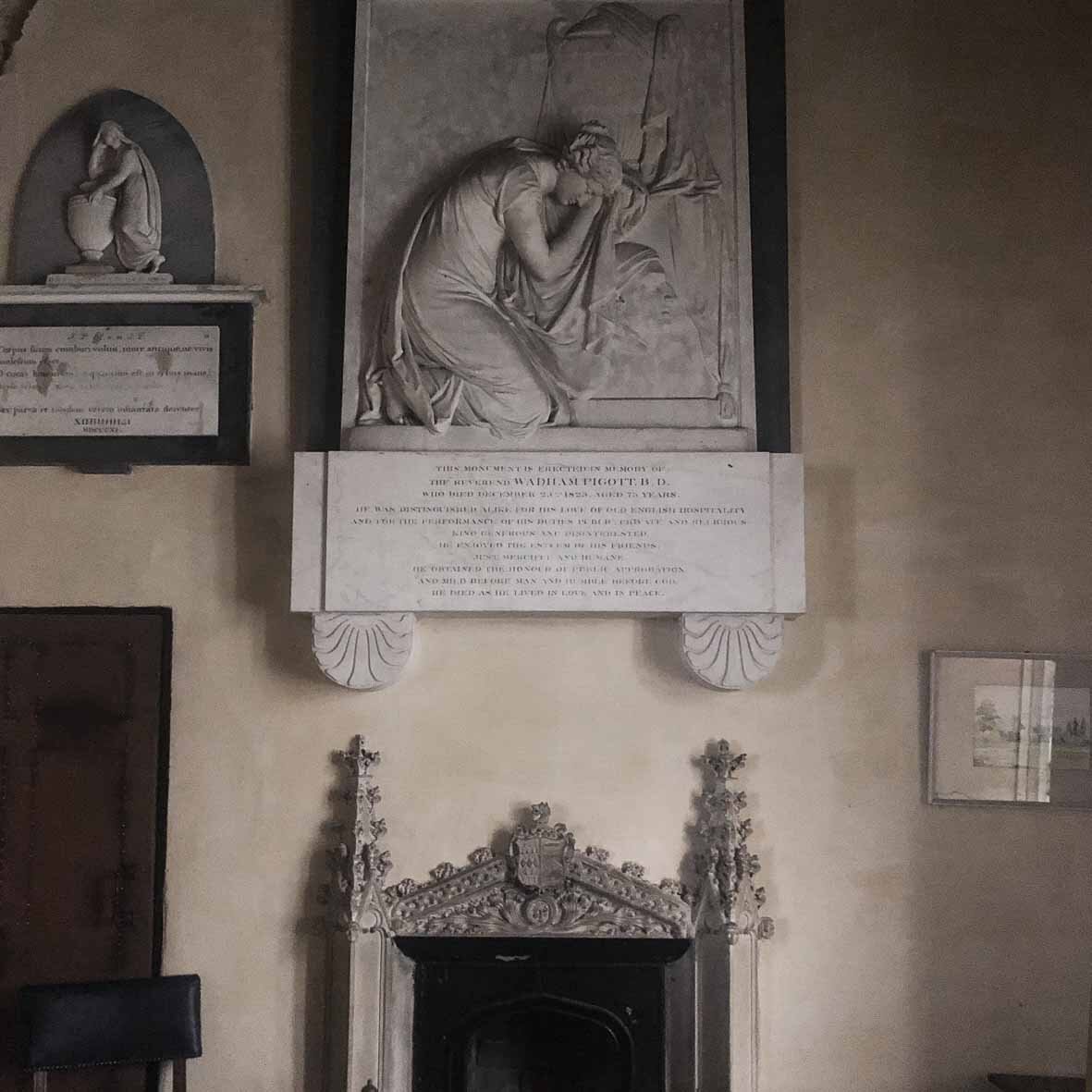

Aldo Rossi imagined the city as a manifestation of the collective memory of its people, with monuments and buildings acting as fragments of this shared history. Similarly, Roland Barthes believed that the Eiffel Tower had transcended its purpose as an object of engineering and had become a synonym for Paris in its totality. In many ways, this is how I feel about St Cuthbert’s. Not because it is necessarily monumental or iconic, but because the monolithic brick massing and deep splayed entrances symbolise this corner of Brislington, South Bristol, and that’s before we mention the moments of celebration, contemplation and reflection that are stored within its walls.

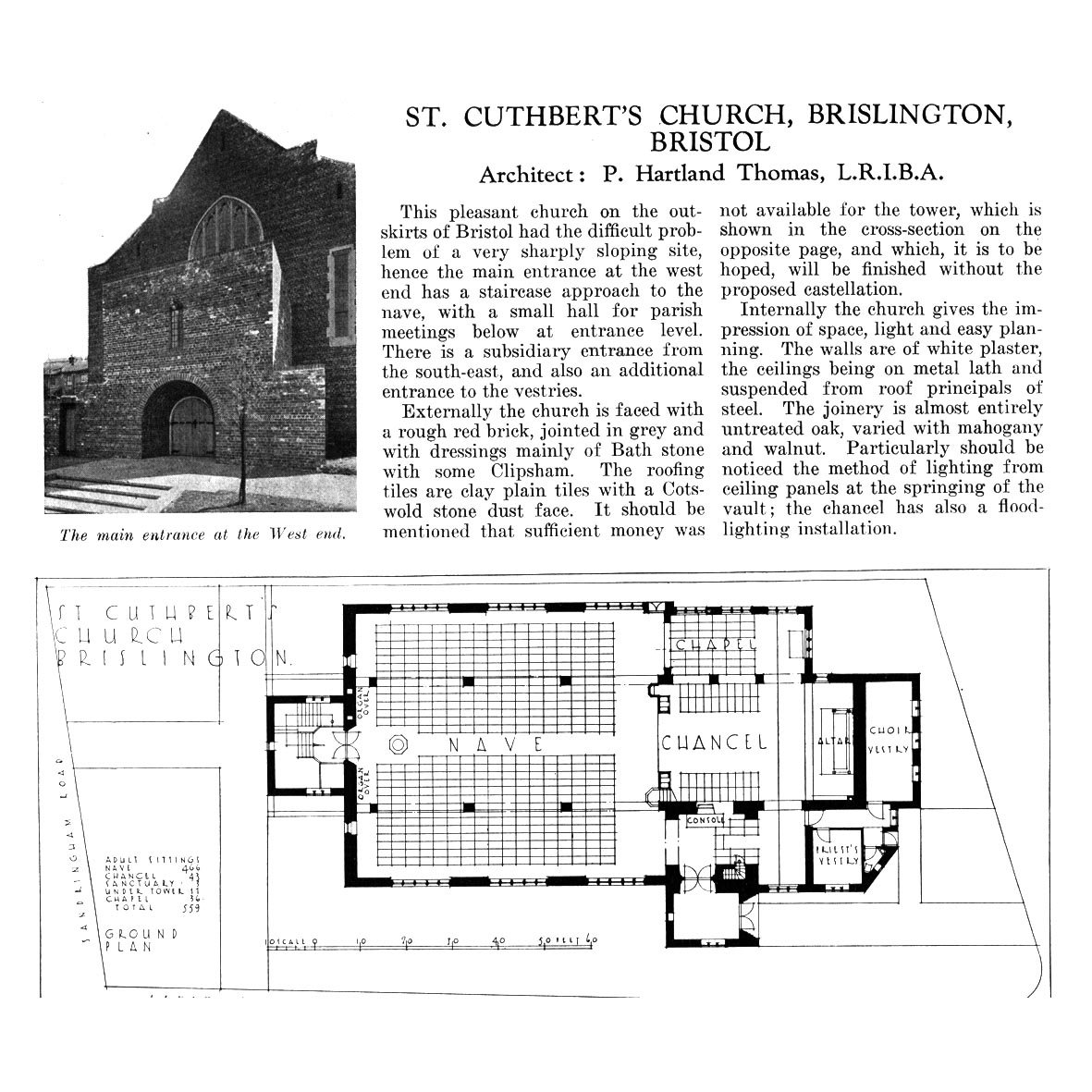

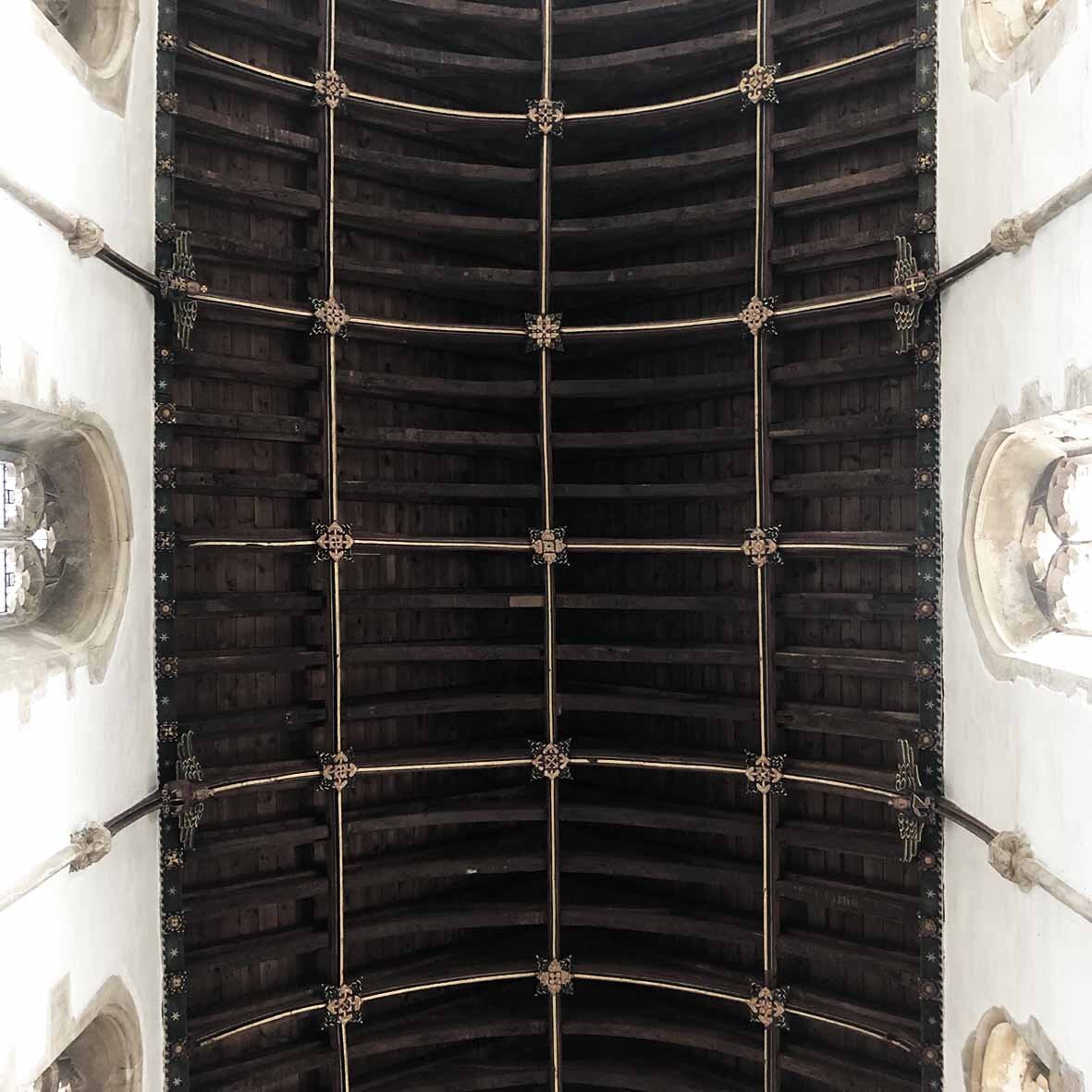

The church was designed by local architect P. Hartland-Thomas and completed in 1933. The building exemplifies the transition of 20th century ecclesiastical architecture – from known sanctified motifs of the Classical and Gothic, towards a vernacular modernism that spoke to an increased civic attitude post-war.

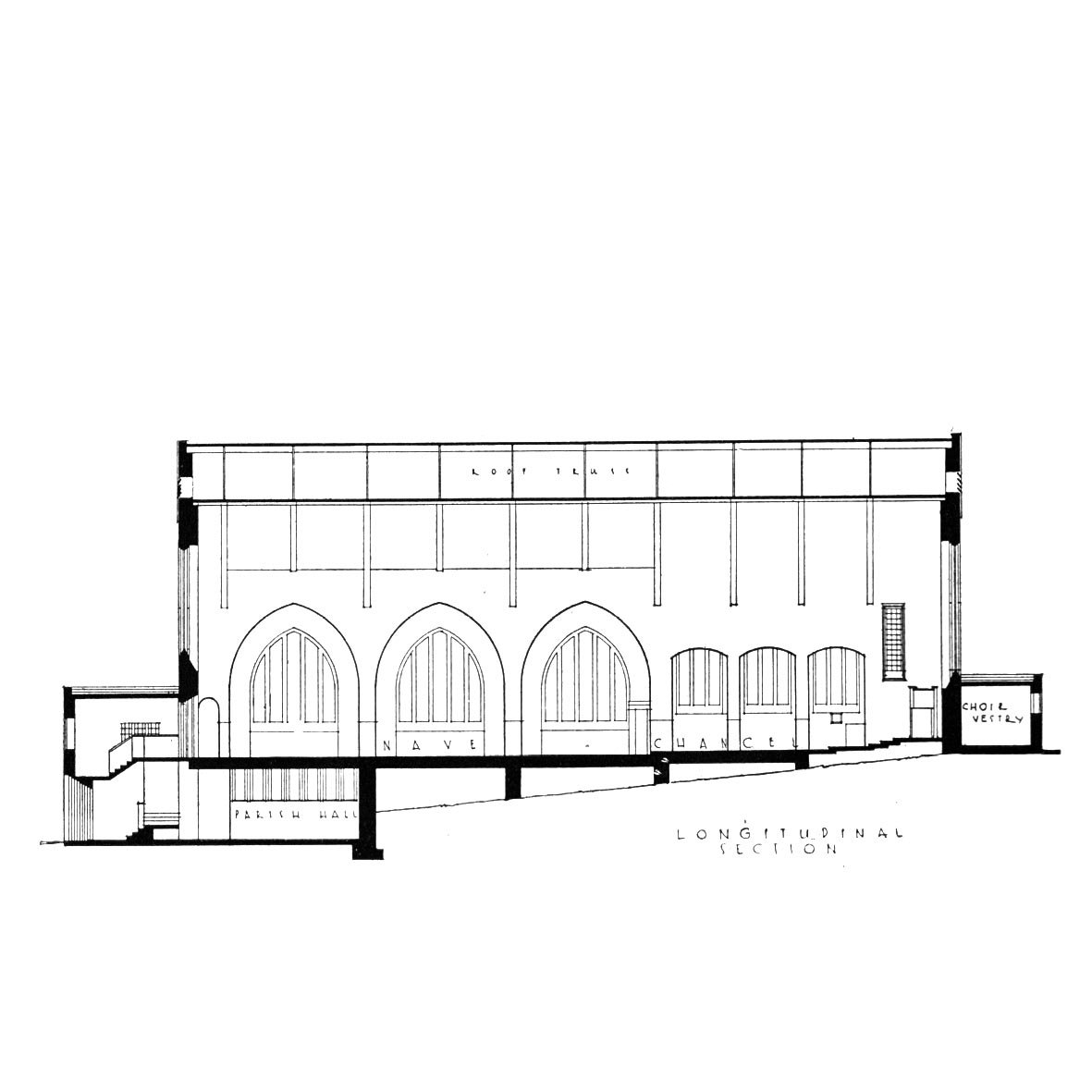

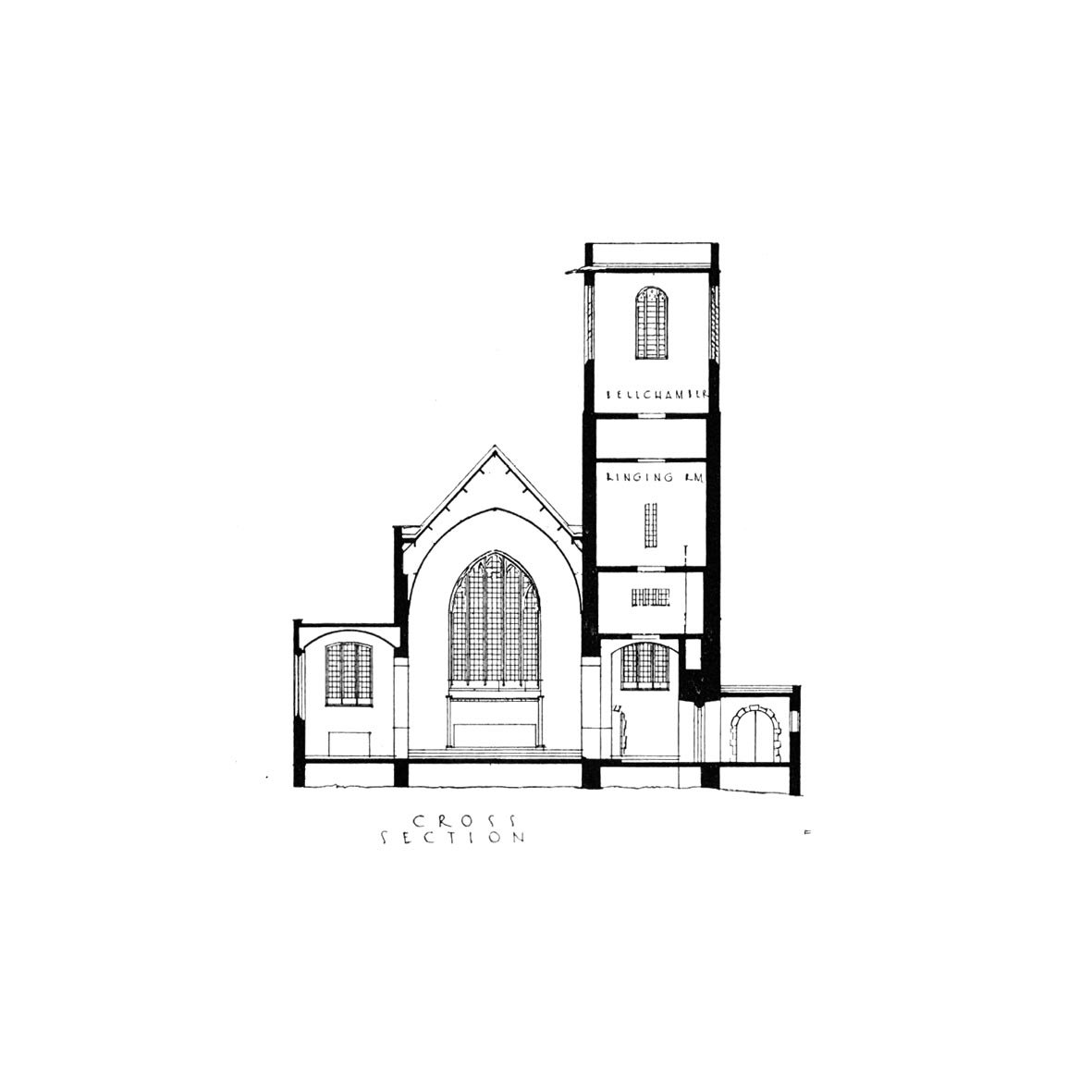

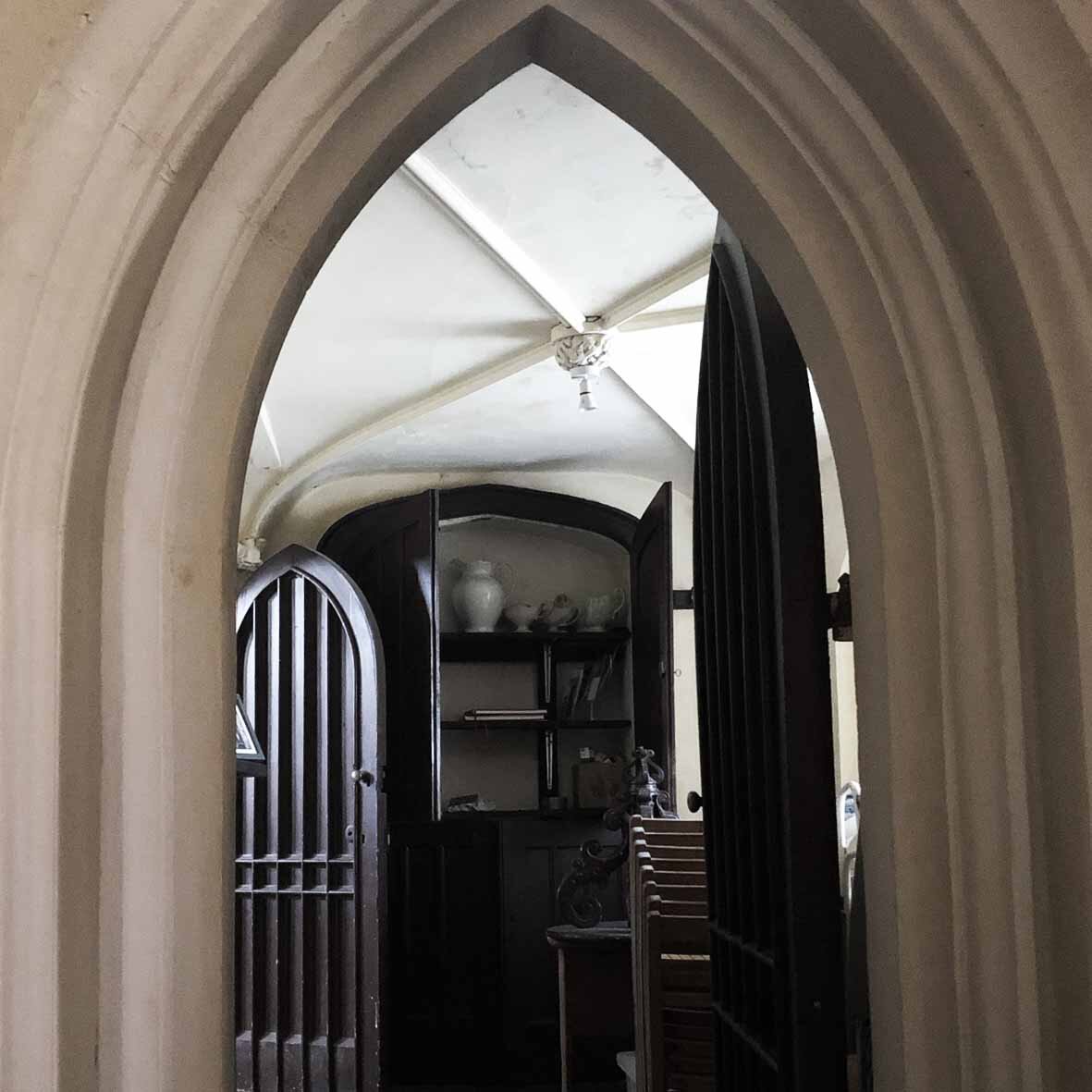

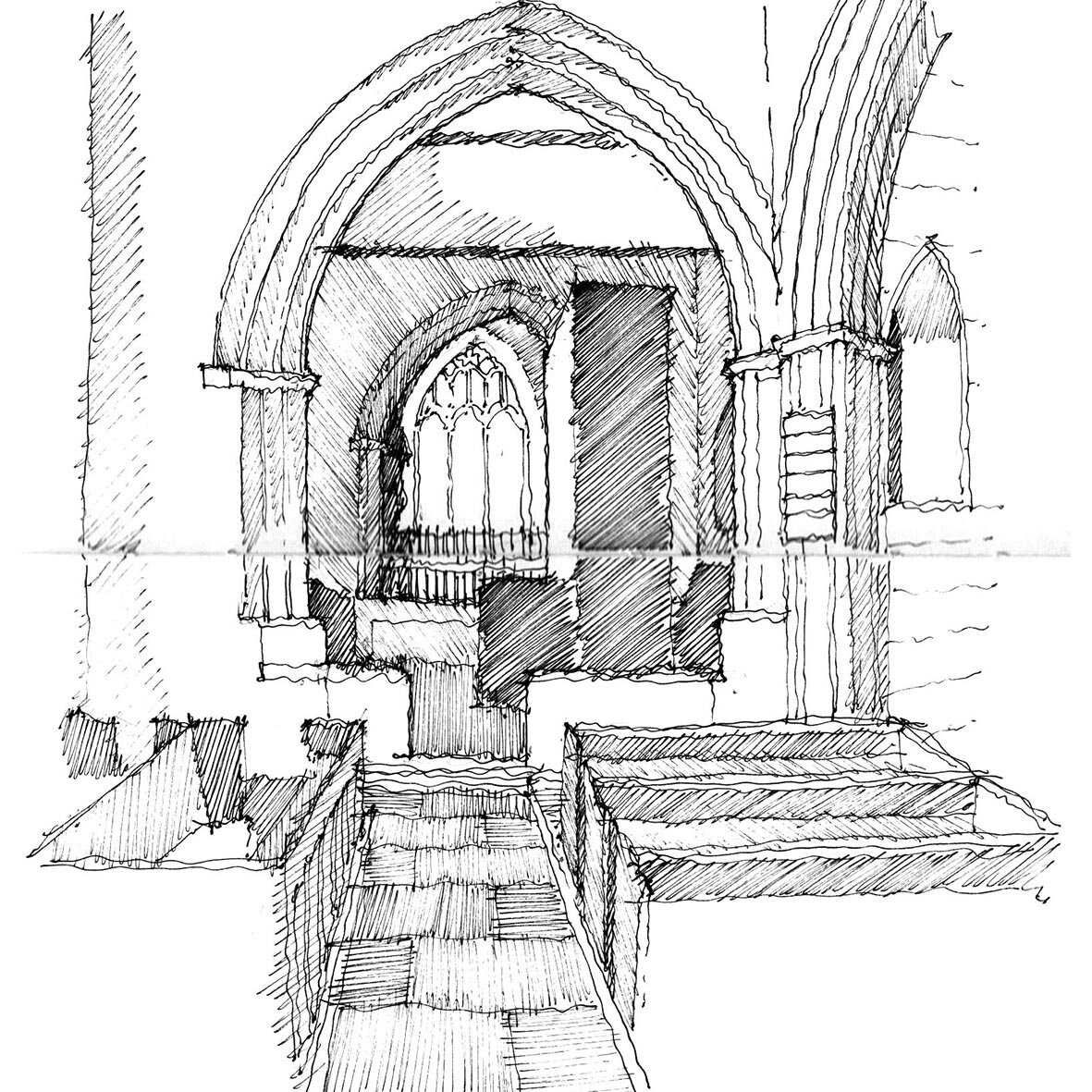

Our ambitions as designers are both emboldened and humbled by the context that we inherit, St Cuthbert’s is further evidence of this. The building is uncompromisingly urban, with its staggered monolithic forms and inviting splayed arch openings accentuated by red brick. A lack of coins in the coffer meant that the tower was never finished to Hartland-Thomas’ designs. This resulted in a staggered massing that unconsciously anticipated the popularity of the campanile later on in 20th century municipal architecture.

In contrast, the interior is reposeful in its simplicity, light shines through large openings and clean unadorned arcades to meet white washed walls. A lack of ornament is mediated through the population of rich, crafted oak furniture that distils the proportion and artistry of medieval screens and tracery. There is a clarity to the design, a culmination of Hartland-Thomas' church work across the city, with similar motifs found at St Michael’s, Windmill Hill and St Oswald’s, Bedminster Down. The church is the most complete remaining example of the architect's work and though it shamefully remains unlisted, we continue to treat it with the respect and responsibility that it deserves.