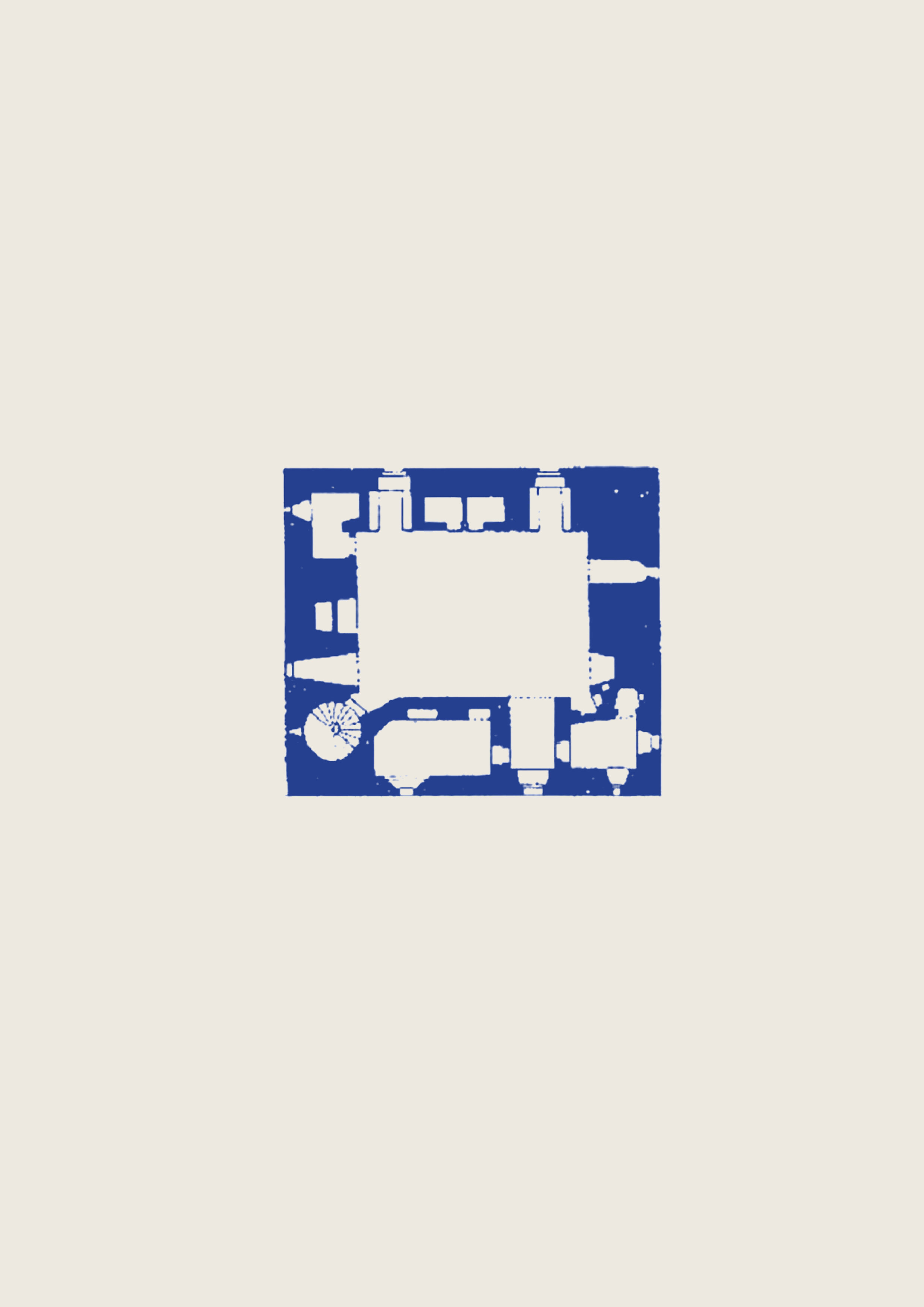

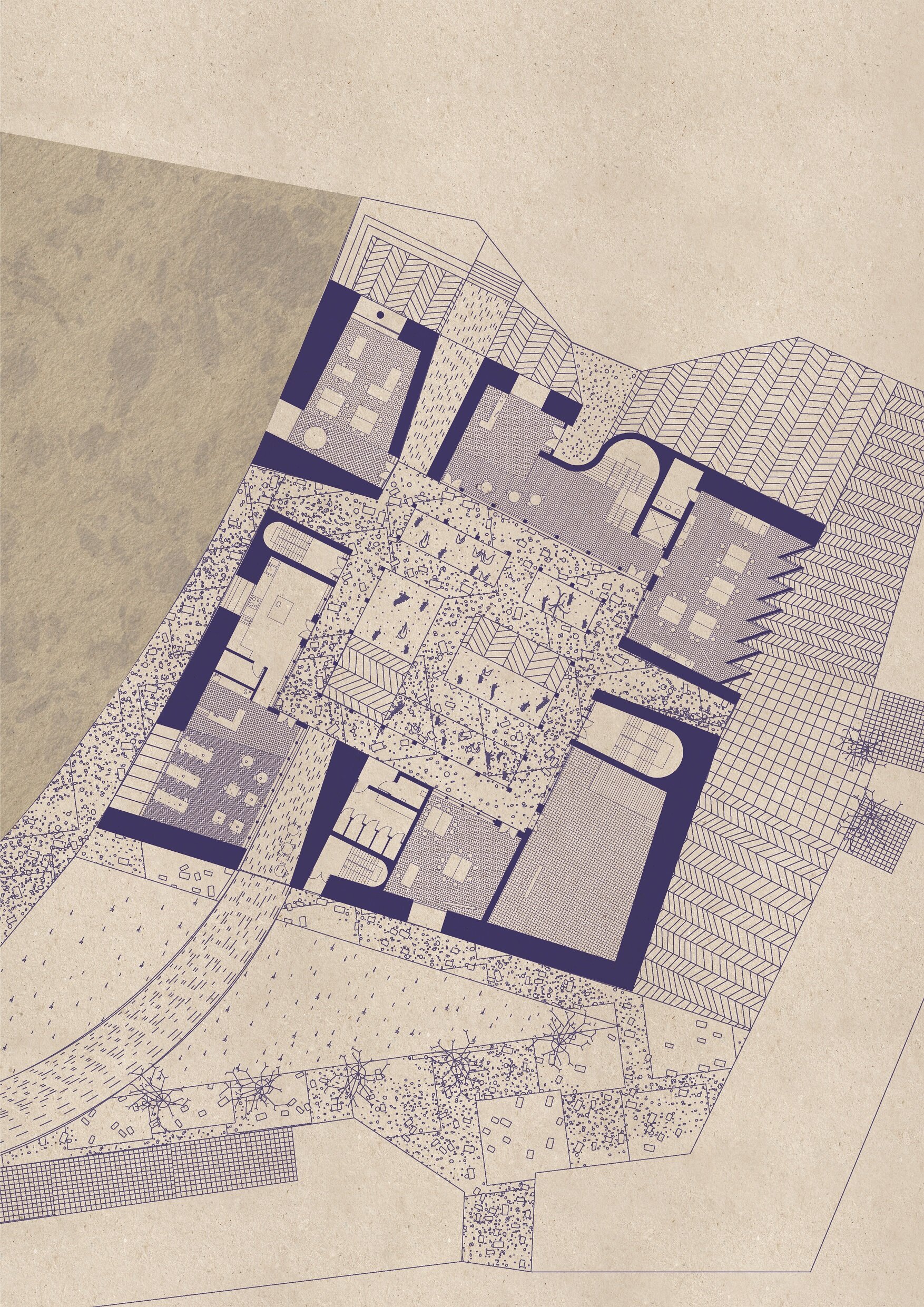

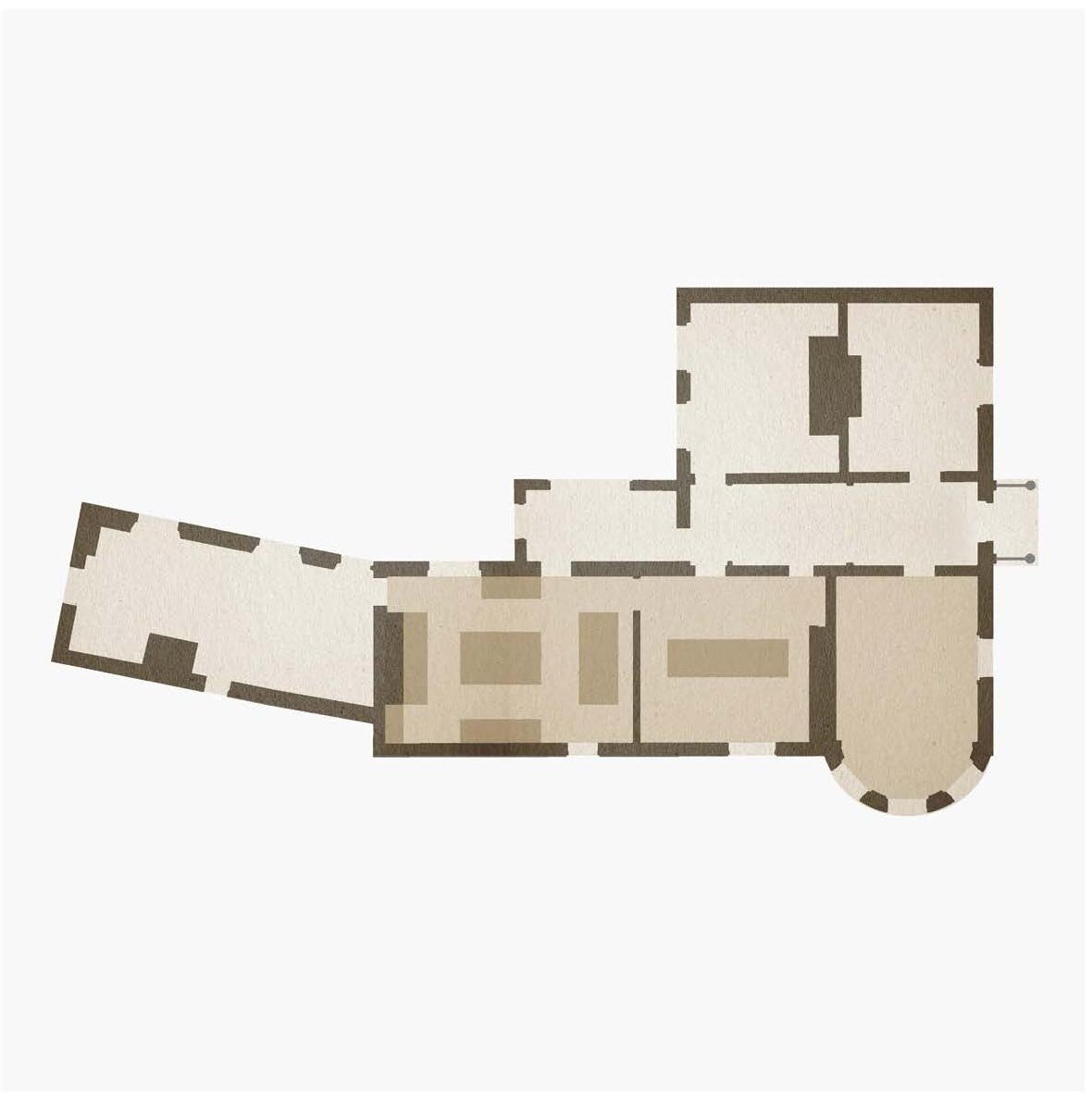

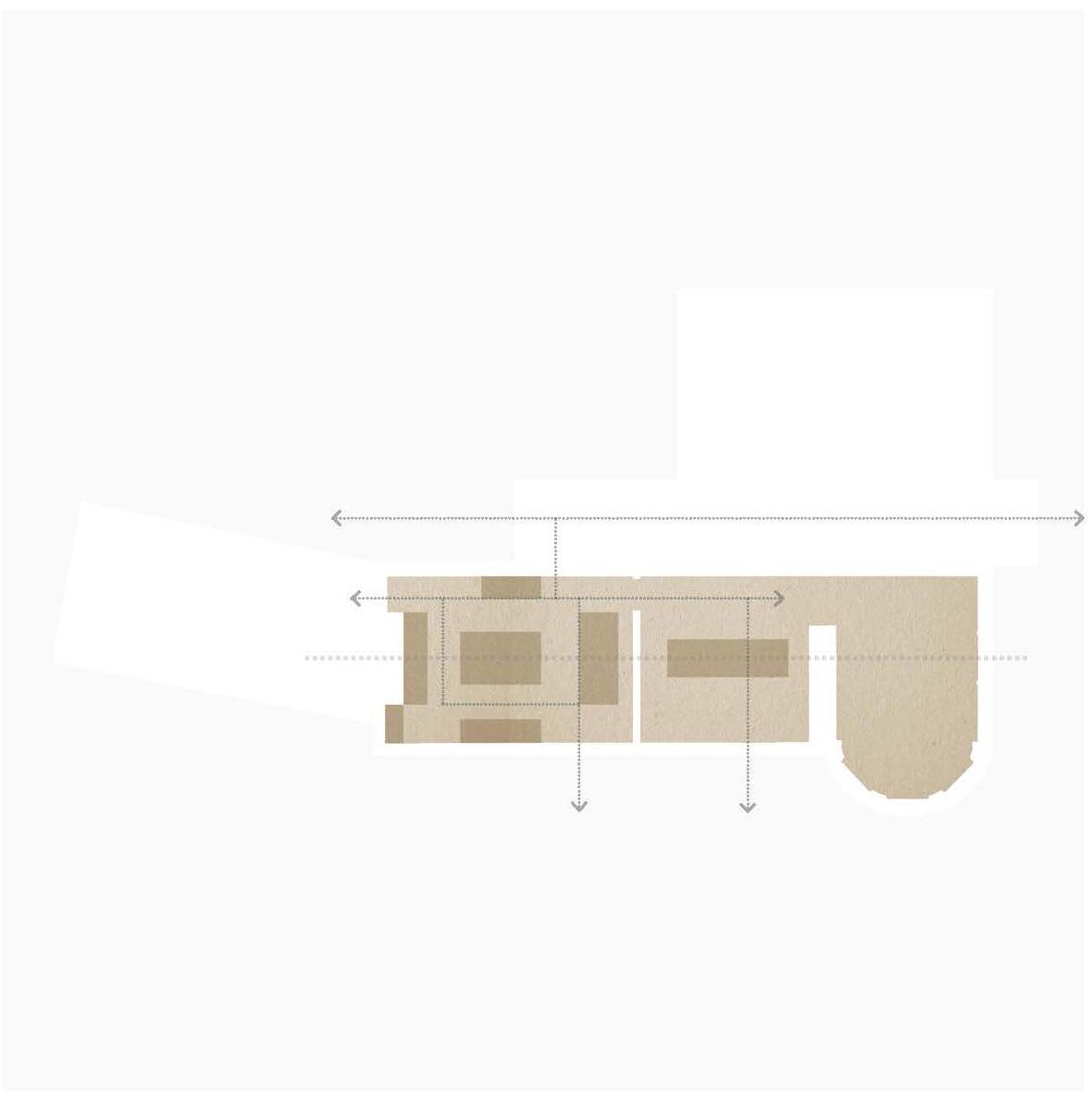

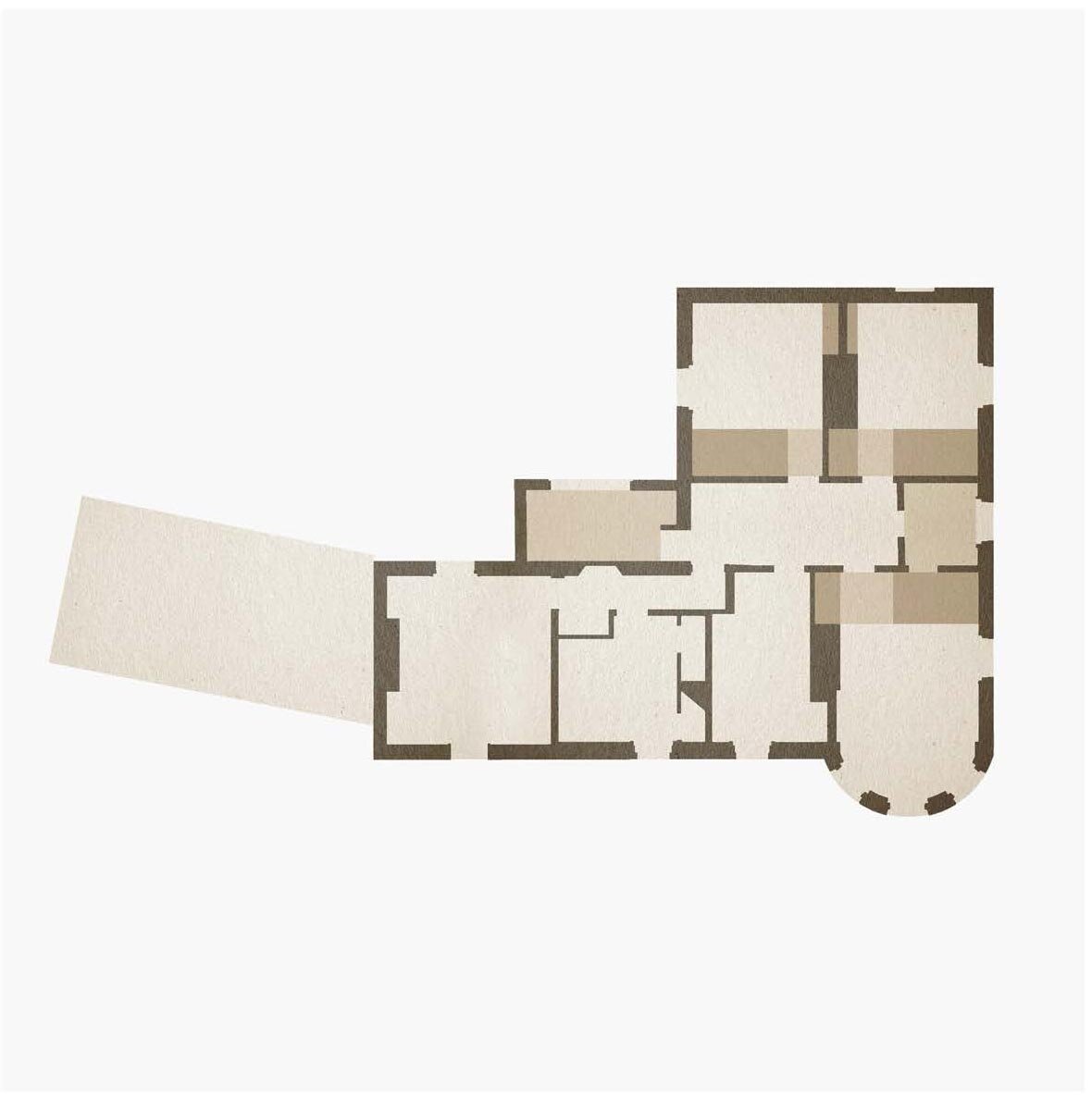

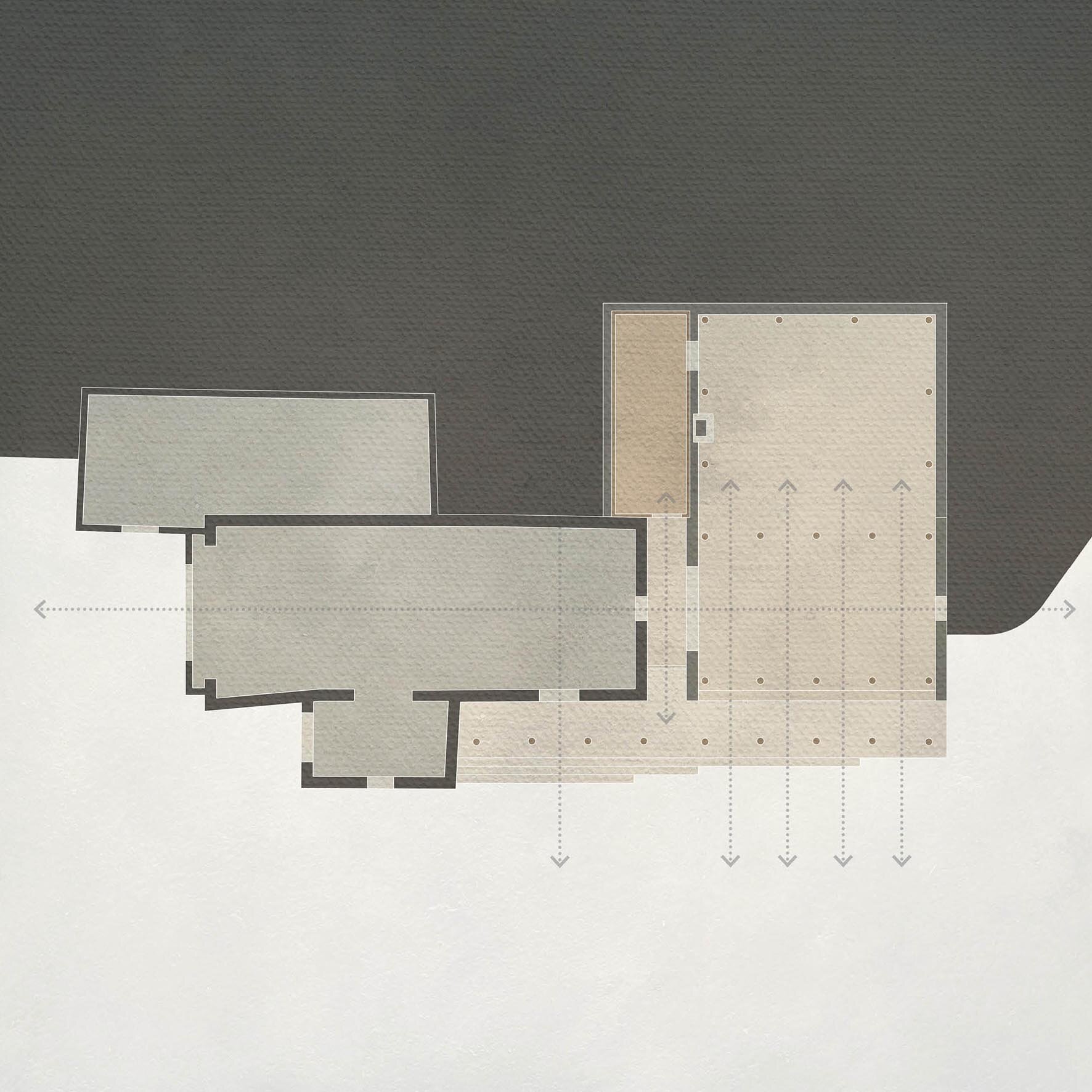

Connolly Wellingham Architects have submitted Listed Building Consent for the conservation and repair of a fire damaged, Grade II* Manor House dating to the 15thC. The initial design exercise sought to establish the pre-fire condition of the perished medieval roof timbers by thorough examination of minimal surviving fabric, before proposing an appropriate replacement structure in green oak.

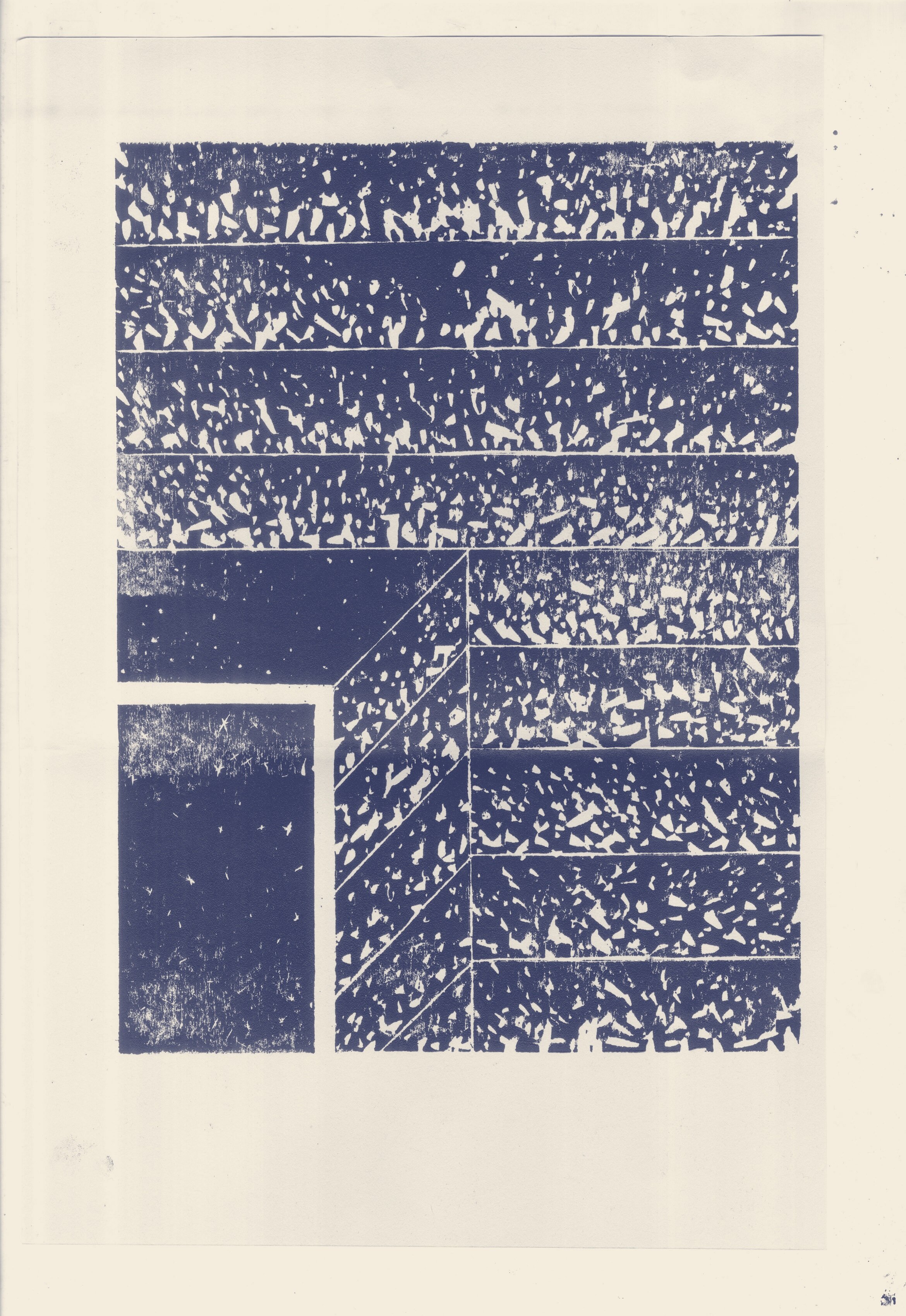

The replacement roof will be finished in timber shingles to match the previous condition, noted in the 1980s listing description. This is believed to have replaced an earlier thatch roof, and is unusual for high status houses of this typology. The damaged condition has uncovered a wide breadth of pragmatically agricultural details, from historic earth mortar on reed lathe and thick roundwood window lintels, to more opportunistic areas of concrete block infill.

Striking the correct balance of historical memory and contemporary performance has made this one of our most technically and philosophically nuanced projects to date.

Determination is due in October.