Anyone keeping a keen eye on the CWa Instagram feed recently will have noticed we have been posting ‘stories’ of photography and sketches capturing the atmosphere and detail of some of the extraordinary historic churches near to us in Bristol and Bath. We were discussing the series in the studio recently – why do we visit these churches, what do we enjoy, how do we capture imagery, why do we feel it is important to share them - and although it is all very informal we felt it could be useful to set out our intent in a blog post for any viewers who are interested to know more. Although at first glance the images repeat similar themes within recognisably familiar buildings, we hope that the curated sequential exploration of each church begins to reveal some of the less tangible beauty that we derive great pleasure from studying. The following are a few themes that recur in our conversations about churches.

1. All churches are the same, no churches are the same

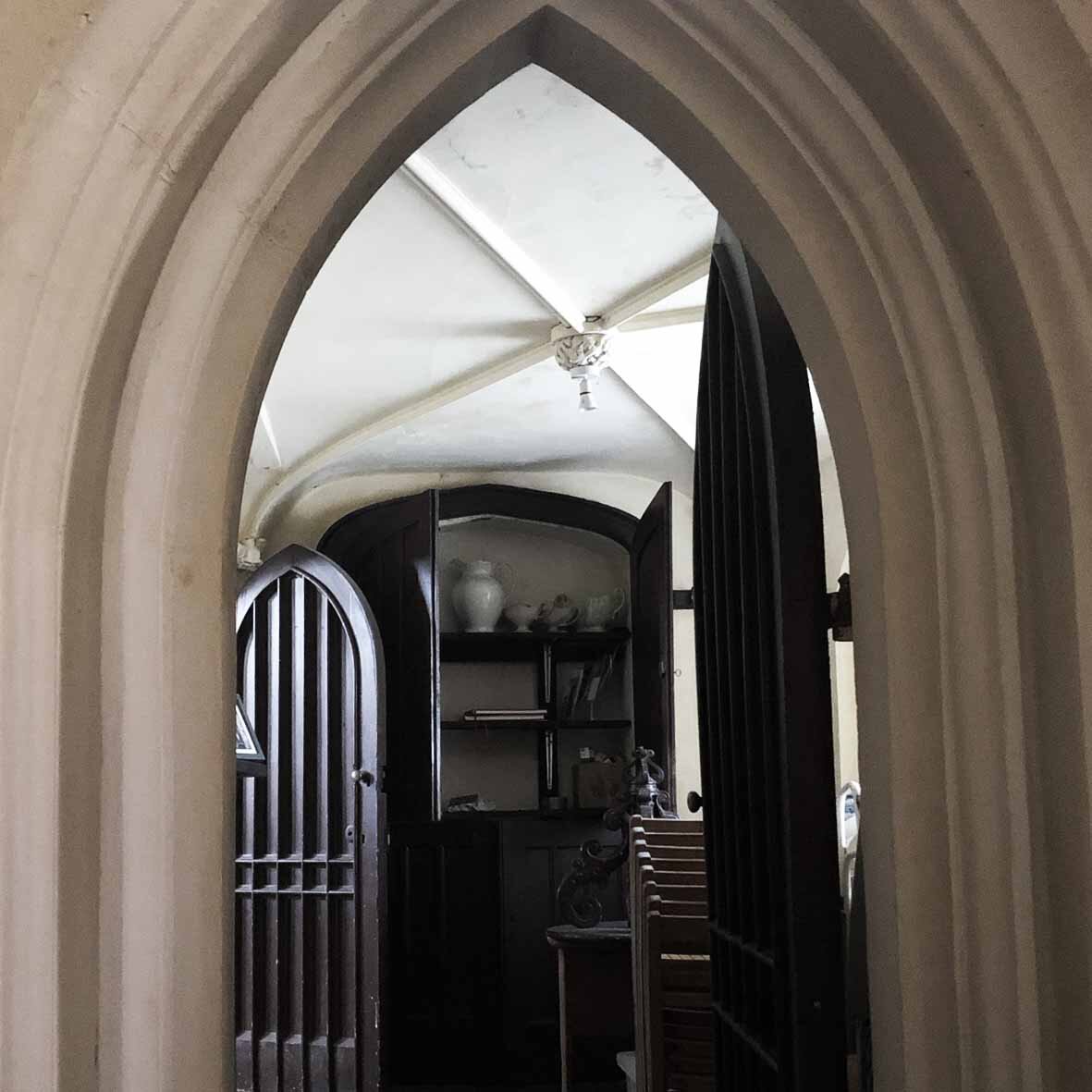

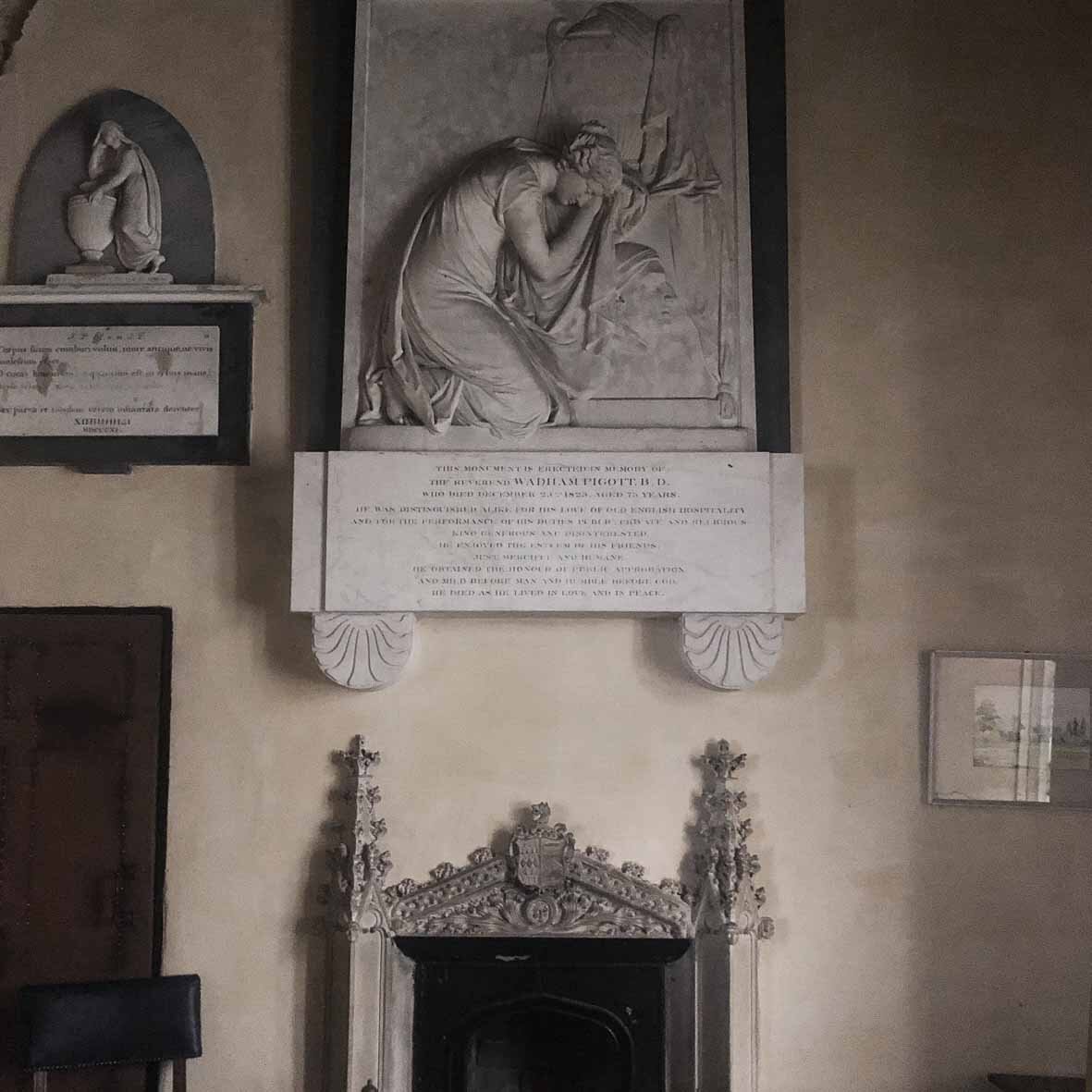

Most Church of England sites will conform to a fairly standard template for the principal arrangement of spaces and their geographical orientation – the altar sits at the east end beneath the high-status east window, the nave is usually entered from the north or south, with a ceremonial door at the west for liturgical occasions, etc. Where an individual church deviates from this standardisation is a starting point for intriguing and unexpected arrangements. There are many physical reasons why this arrangement might change – the topography of a hillside, the prevailing direction of approach on foot, an ancient tree, an earlier structure. A simple change like the location of a porch results in a ripple effect of reactions throughout the rest of the space – the placement of the font will respond to the location of the door, the route from the vestry to the font may influence the direction of an aisle through a set of pews, the placement of a lectern or pulpit will respond to the distribution of the pews. These chain reactions are furthered when items are altered, added or moved – a redecoration, a high-status monument, a legacy fund for a memorial pew. Additive changes may cover over earlier conditions (fitted furniture or wall memorials), but relocations are equally likely to uncover them (forgotten floor ledgers, scraps of wall painting).

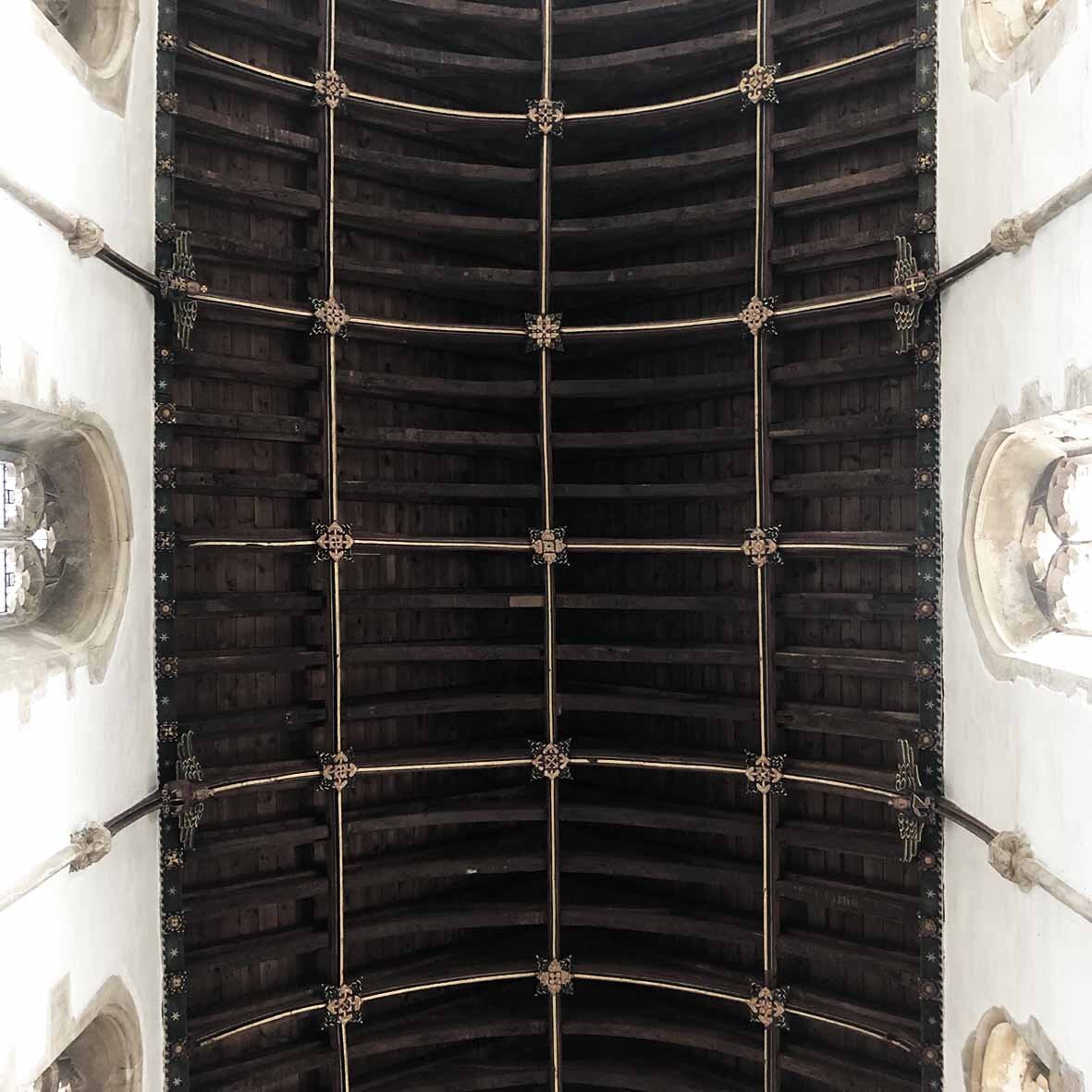

2. A church interior is like a city

We are fascinated by the parallels that occur across scales in architecture, and we actively nurture these compelling ambiguities in the new work we design. All of the reasons why we love the jumbled accretion of an historic city can be found in the evolution of a historic church interior. Consider a church nave as a public square (which we would strongly argue it is) – the windows and monuments of the outer walls are the facades of the public fronting buildings, each one with their own proportion and logic, with their differences sitting comfortably alongside one another and often in direct dialogue. The movement or introduction of furniture within this void becomes an urbanism exercise of desire lines, eyeline vistas, hierarchy, subservience, connection and separation – liturgically as well as physically.

The often ruthless abutment of layered phases that we see in historic cities – where ownership boundaries dictate the limits of wholesale change – is equally evident within the churches; the frugal acceptance of found condition is acknowledged as the correct and ethical response to a congregation’s forefathers. This is particularly evident in the smallest and oldest churches, where the jostling adjacency of subsequent interventions create incredibly dynamic compositions – richly awkward interstitial spaces that can only be made through hundreds of years and by hundreds of hands. The repetition of architectural detailing in miniature reinforces this sense of scalelessness; fine joinery adorned with columns, arches and crenellations.

In terms of our conservation work this illustrates well the importance of maximum fabric retention – or where potential loss is justified and approved as necessary to a church’s future, that new work can retain a trace or memory of a former phase.

3. A church widens perspective

This final theme is less architectural and more social. Parish churches are the physical archive of rural village life, and although not every name gets carved into a ledger or gravestone, every hand contributes to the weathering of the pew end and every foot leaves its mark on the porch step. Whether or not you have faith, a church interior holds these everyday physical traces of humanity (the reality) against the backdrop of that humanity’s highest endeavours of devoted craftsmanship (the aspiration for meaning). Sitting in these quiet and still spaces is an exercise in widening perspective – whether you want to call that prayer, meditation or mindfulness. Cultivating an interest in the architectural and social understanding that a parish church can offer is then expanded by the mind-boggling abundance of this typology – over 16,000 in the Church of England alone, before accounting for other denominations and other countries within the British Isles. As you would expect the local varieties we see in church architecture as we travel from diocese to diocese is as subtle yet identifiable as the vineyards of wine regions. The perspective widens further.

Much of this will not be revelatory to readers of this blog or followers on our Instagram, but if you enjoy seeing the imagery we share, then perhaps the above will help enrich your reflections. If nothing else perhaps it will encourage you to stop off and see what you can find next time you are taking the scenic road and stumble onto an unexpected spire or lychgate. I end with a recap from a few recent posts.

Charlie

St Nicholas, Brockley. 12thC. GII*

St James, Cameley. 12thC. GI

St Mary, Yatton. 13thC. GI