A recent discussion in the studio saw us debating our all time favourite adaptive reuse projects, and I thought the results would make for an interesting set of journal articles – as well as a good chance to keep our minds moving during these bizarre times of industry-wide inactivity. There are many buildings I have visited over the years that could lay claim to the top spot, but I wanted to kick the series off by sharing some photos and drawings of the Basilica di Santa Maria delgi Angeli e dei Martiri.

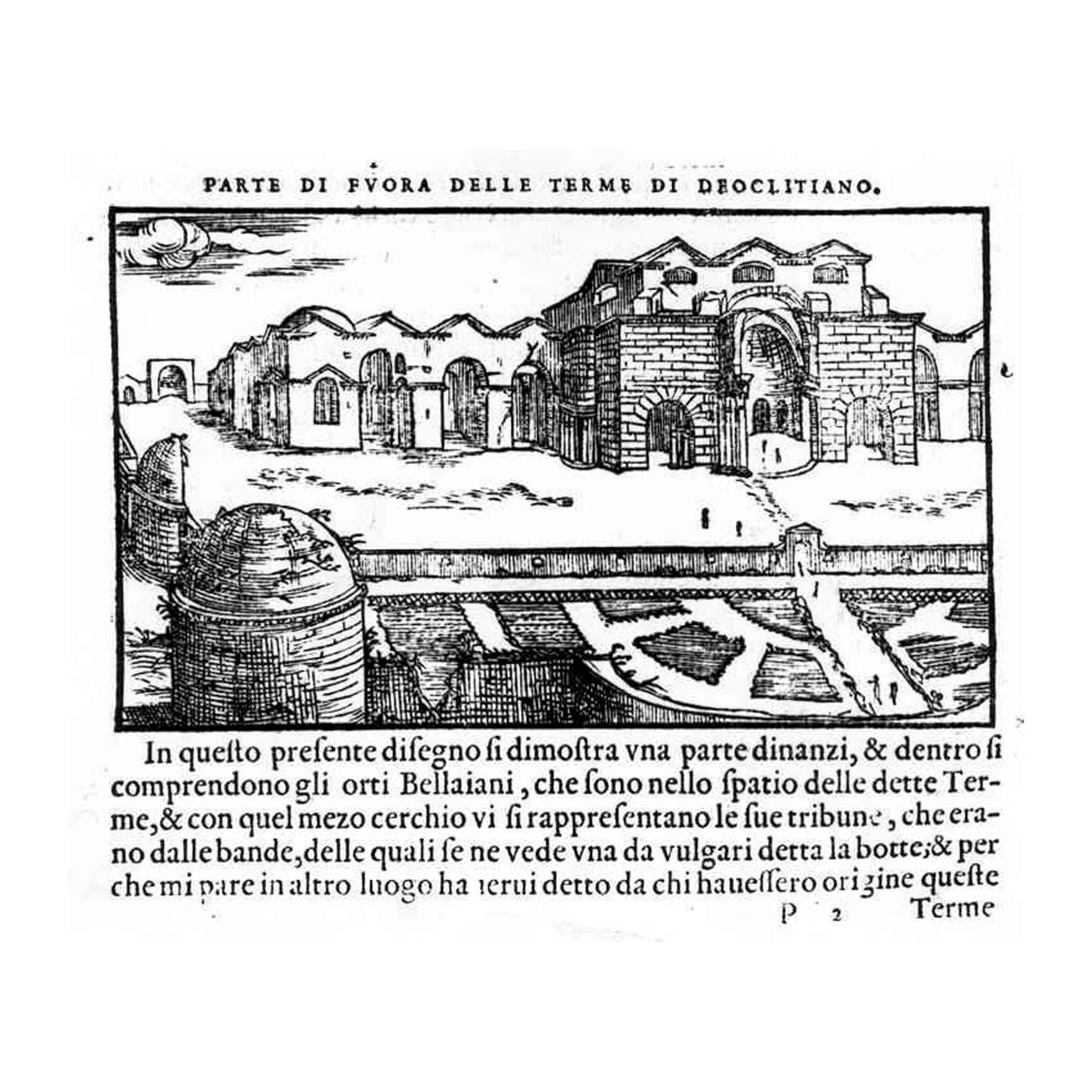

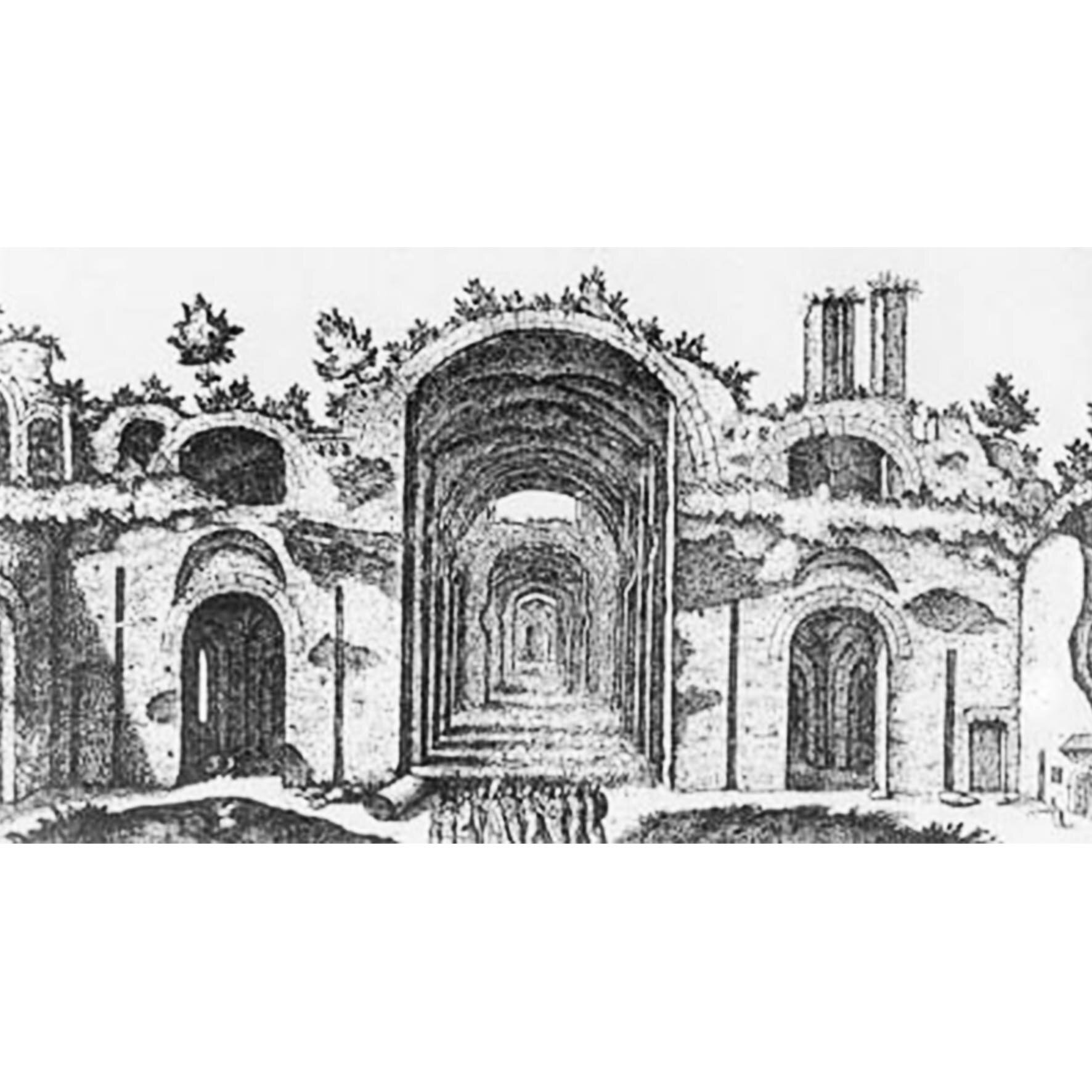

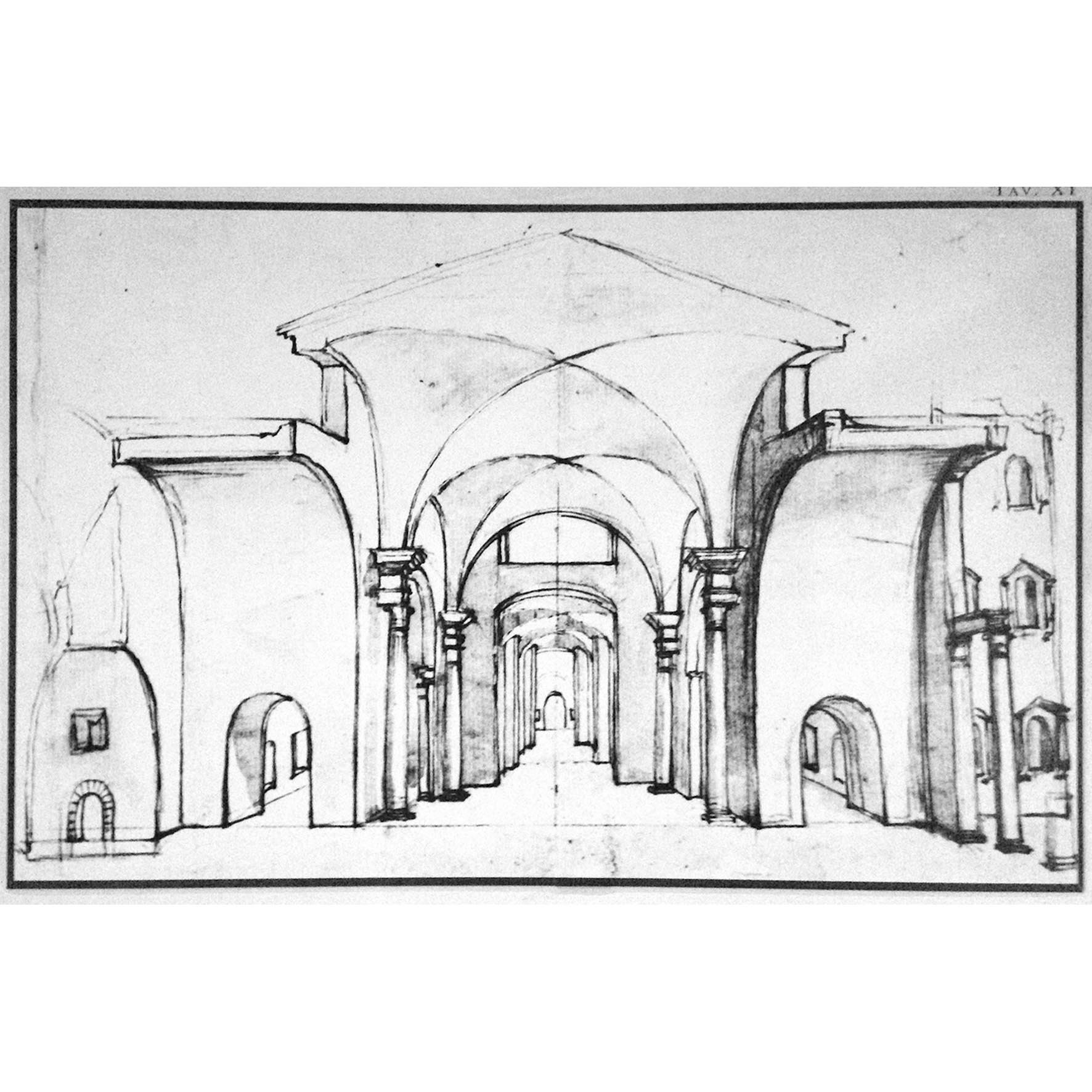

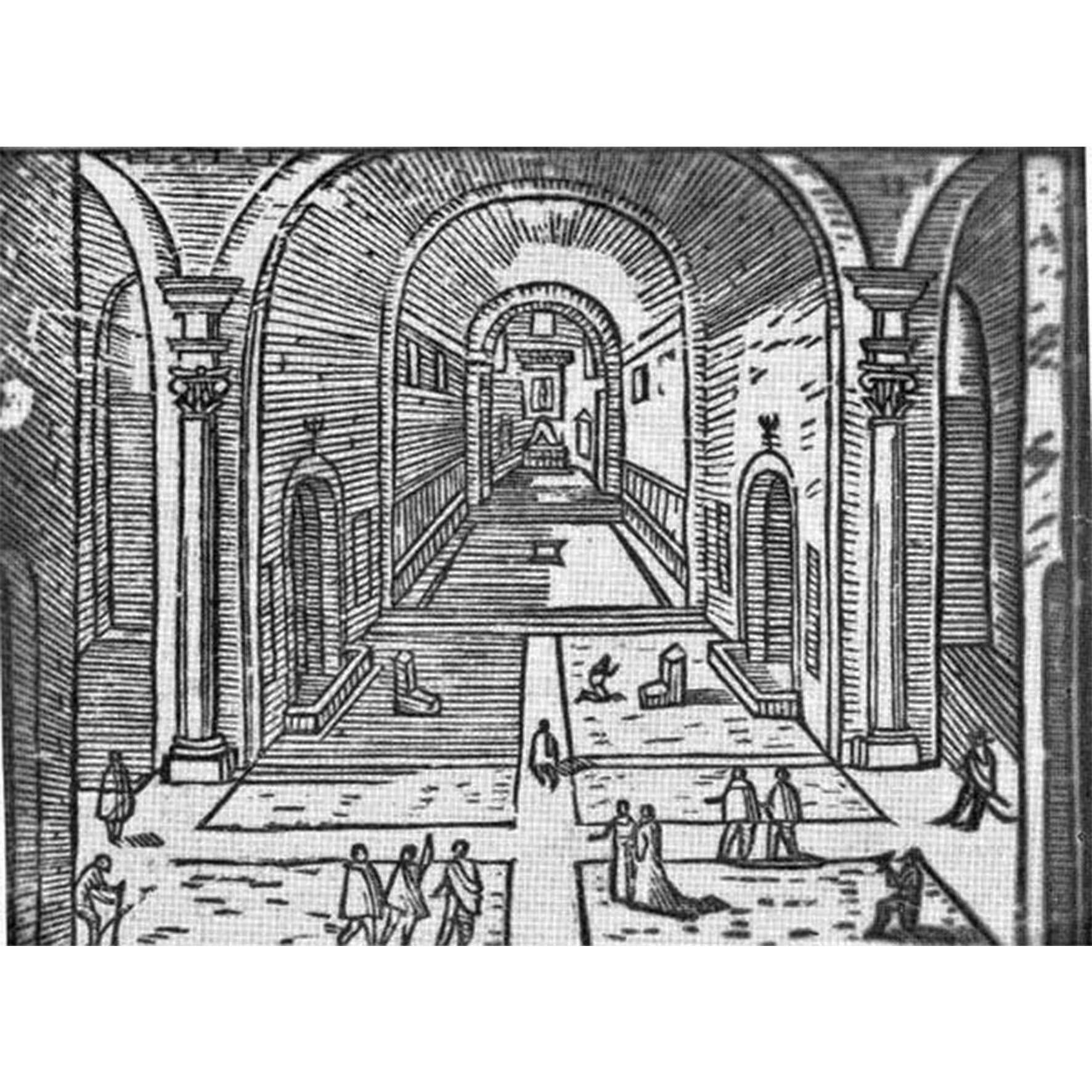

To start the story properly we must begin with the construction of the Great Baths of Diocletian, between 298 and 306 AD at the top of Rome’s Viminal Hill. The site was the largest and most ambitious thermal baths in the Roman world when it was built; a sprawling complex of domes and vaults housing hot pools, cold pools, gymnasia, civic meeting spaces and gardens arranged around a vast central frigidarium. As well as playing a key function in the health and hygiene of the populace, it was the heart of community life. The baths fell into disuse when the aqueduct that fed its water supply was destroyed during a sack of the city in the 5th Century. For the next thousand years the baths stood as an increasingly precarious ruin, as generations of Romans mined the structure for valuable construction materials.

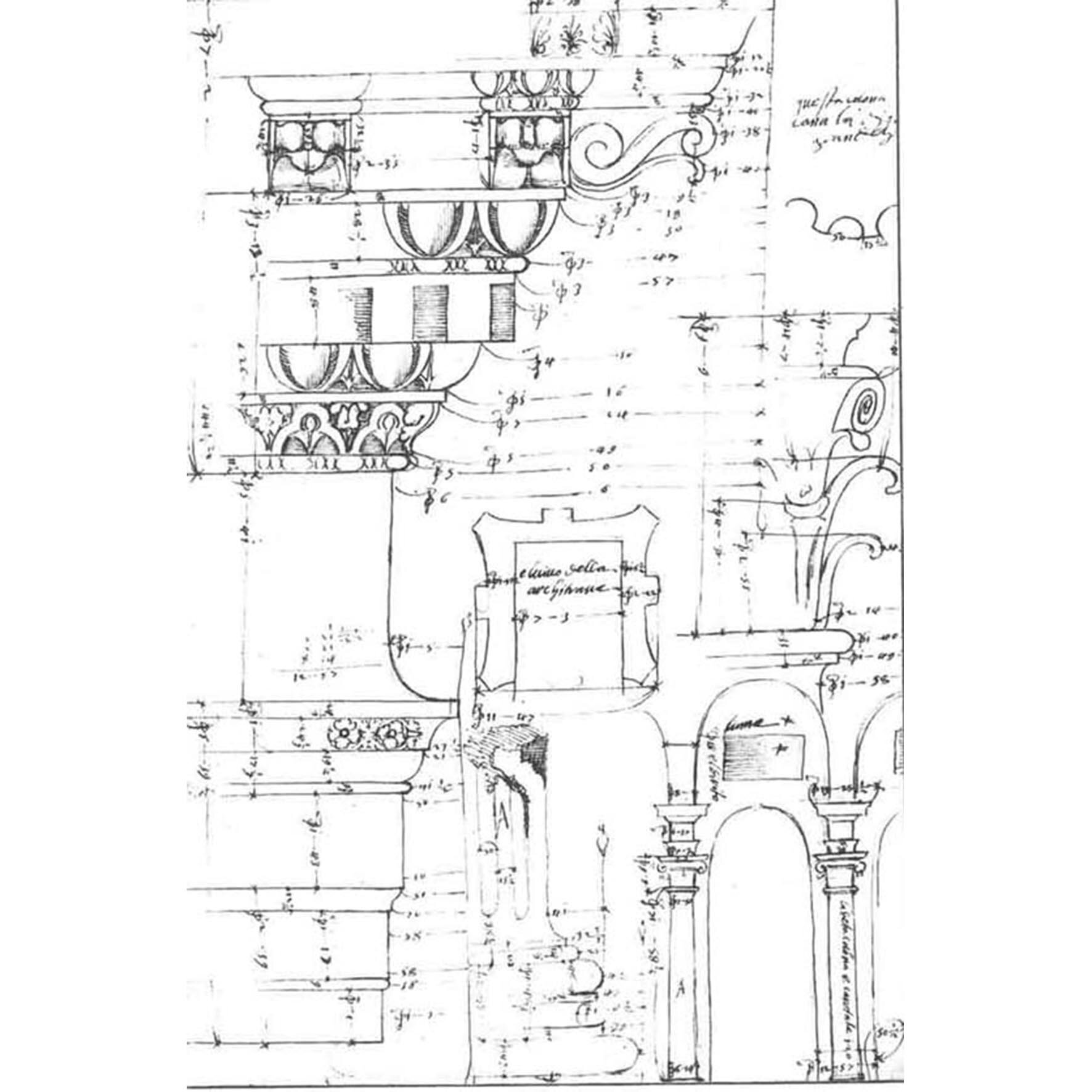

Legend has it that the idea to convert the ruin into a church came to a Monk named Loreto Antonio Lo Duca following a vision received in 1541, when he saw a bright shining light emitting from the central hall of the crumbling edifice. It took another twenty years (and the succession of two new Popes), before designs were completed and works began. Michelangelo Buonarotti was appointed to oversee the design by Pope Pius IV, key to which was creating an appropriately dignified architectural setting for Pius’ own tomb. By this time Michelangelo was well into his late eighties, and consumed with his work at Saint Peter’s Basilica.

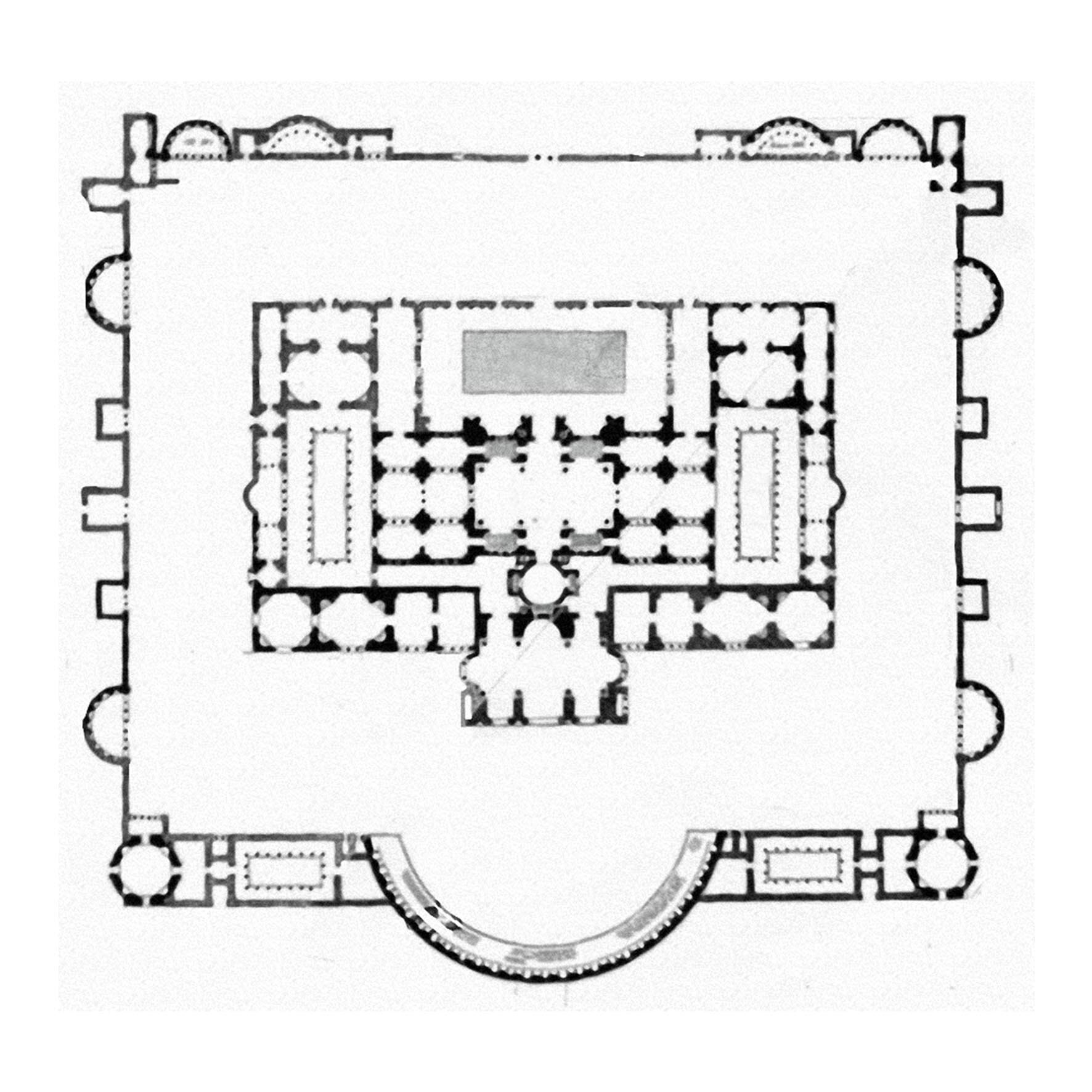

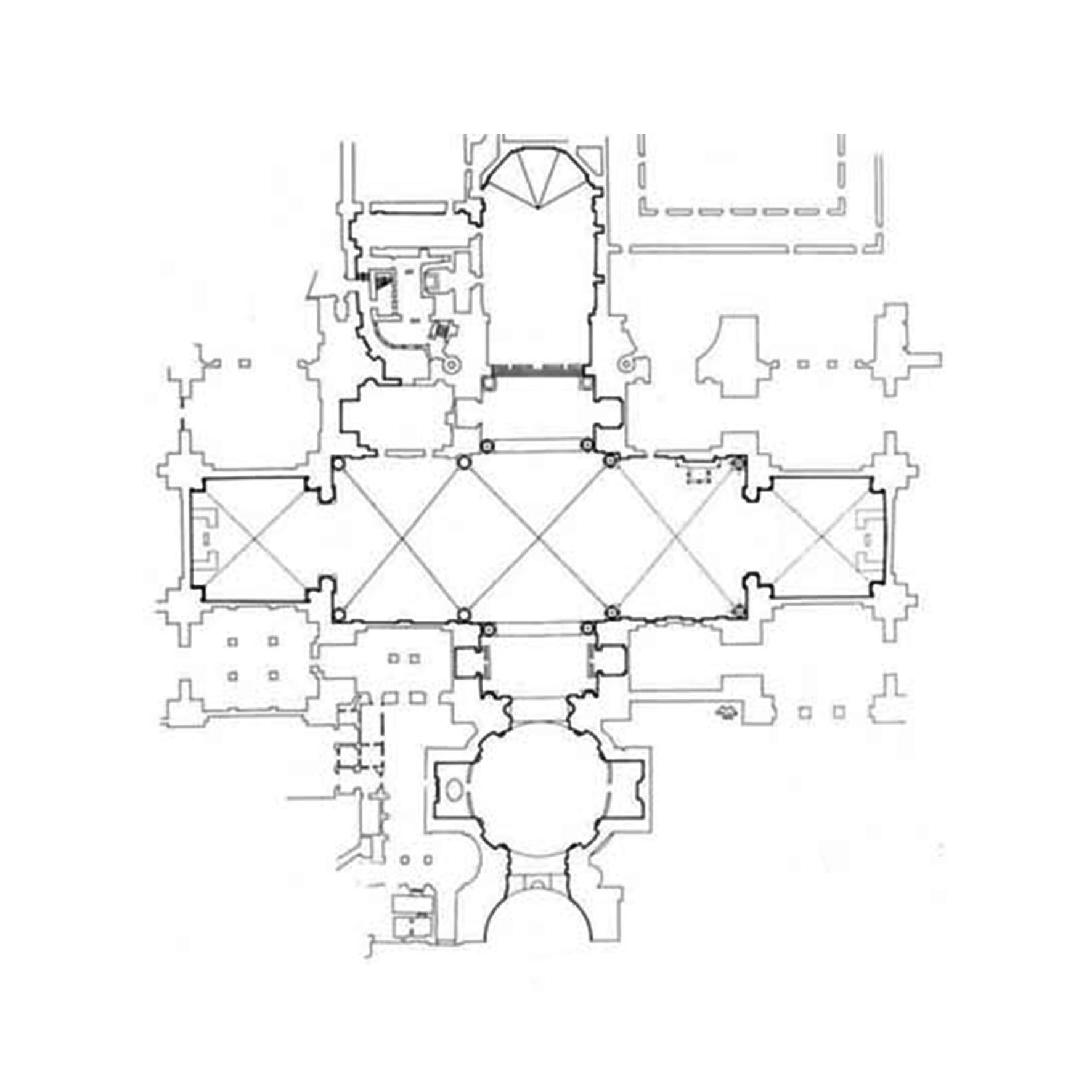

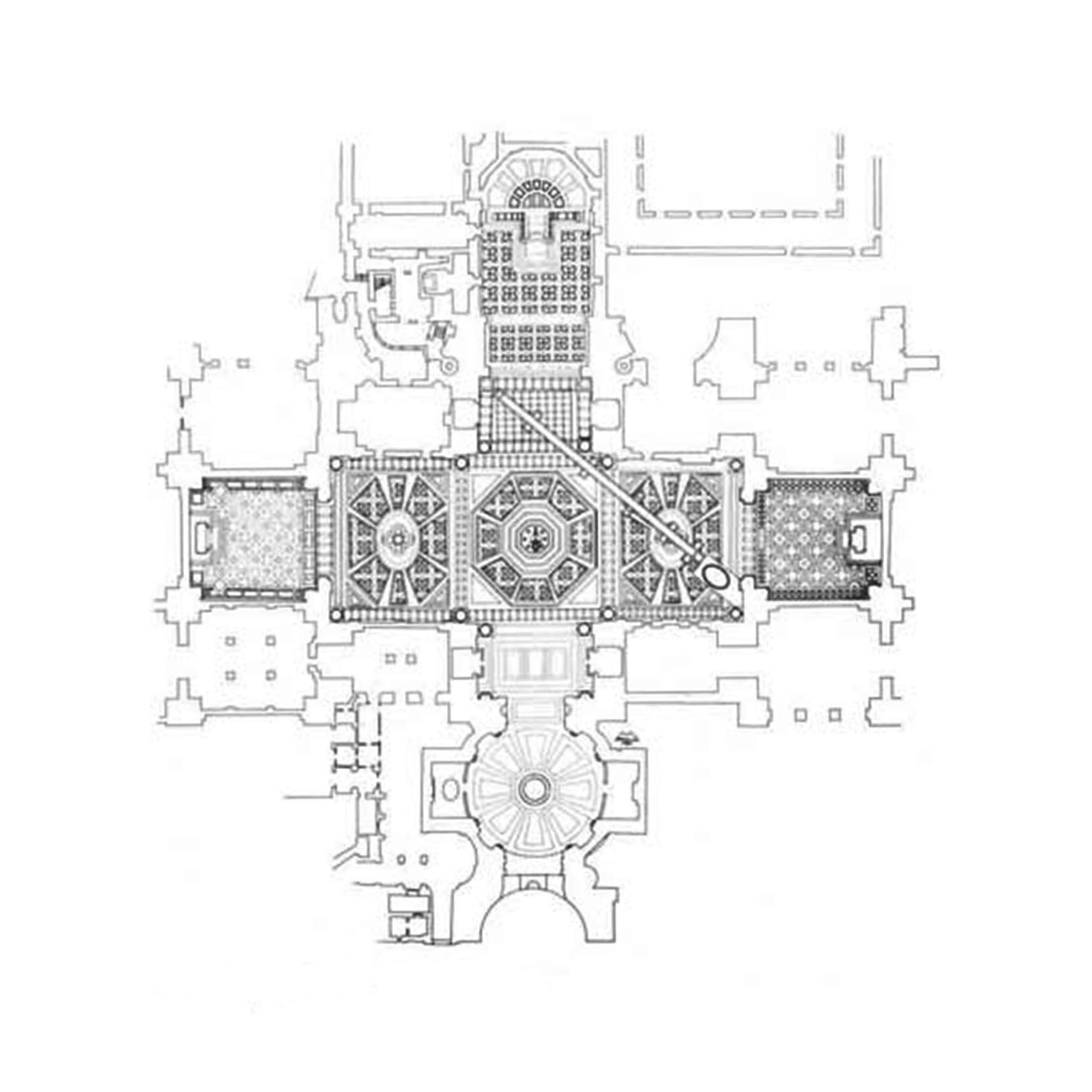

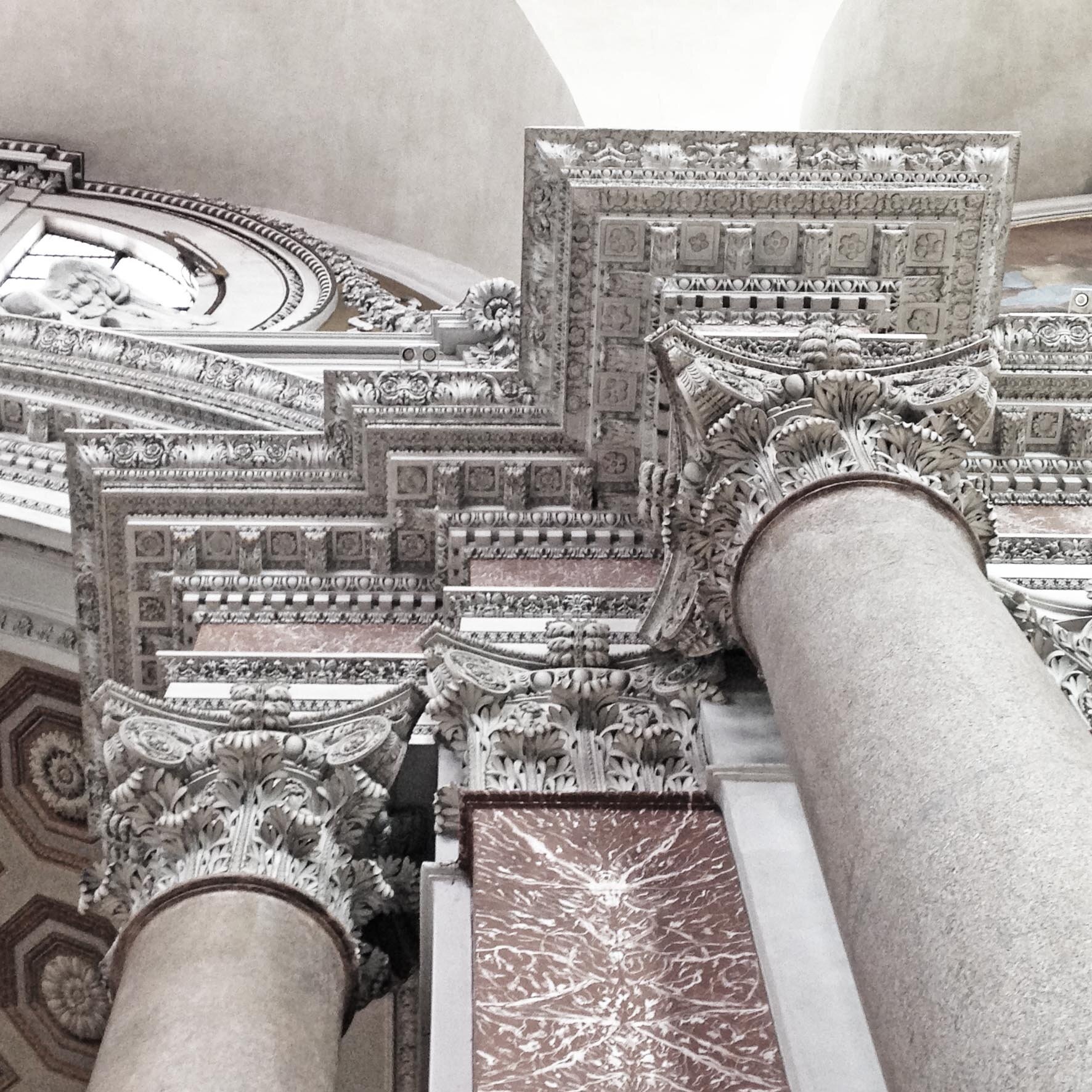

Much of the interior today is the result of Luigi Vanvitelli’s baroque overhaul in the 1750s (including a decorative marble floor with an inlaid sundial illuminated by light streaming through a small hole in the roof), so it is difficult to know how sparse or elaborate Michelangelo’s scheme was. We do know that the arrangement of liturgical spaces in amongst the ruined baths remains largely true to his 16thC designs; a Greek Cross of four equal transepts, centred on the remains of the vast frigidarium.

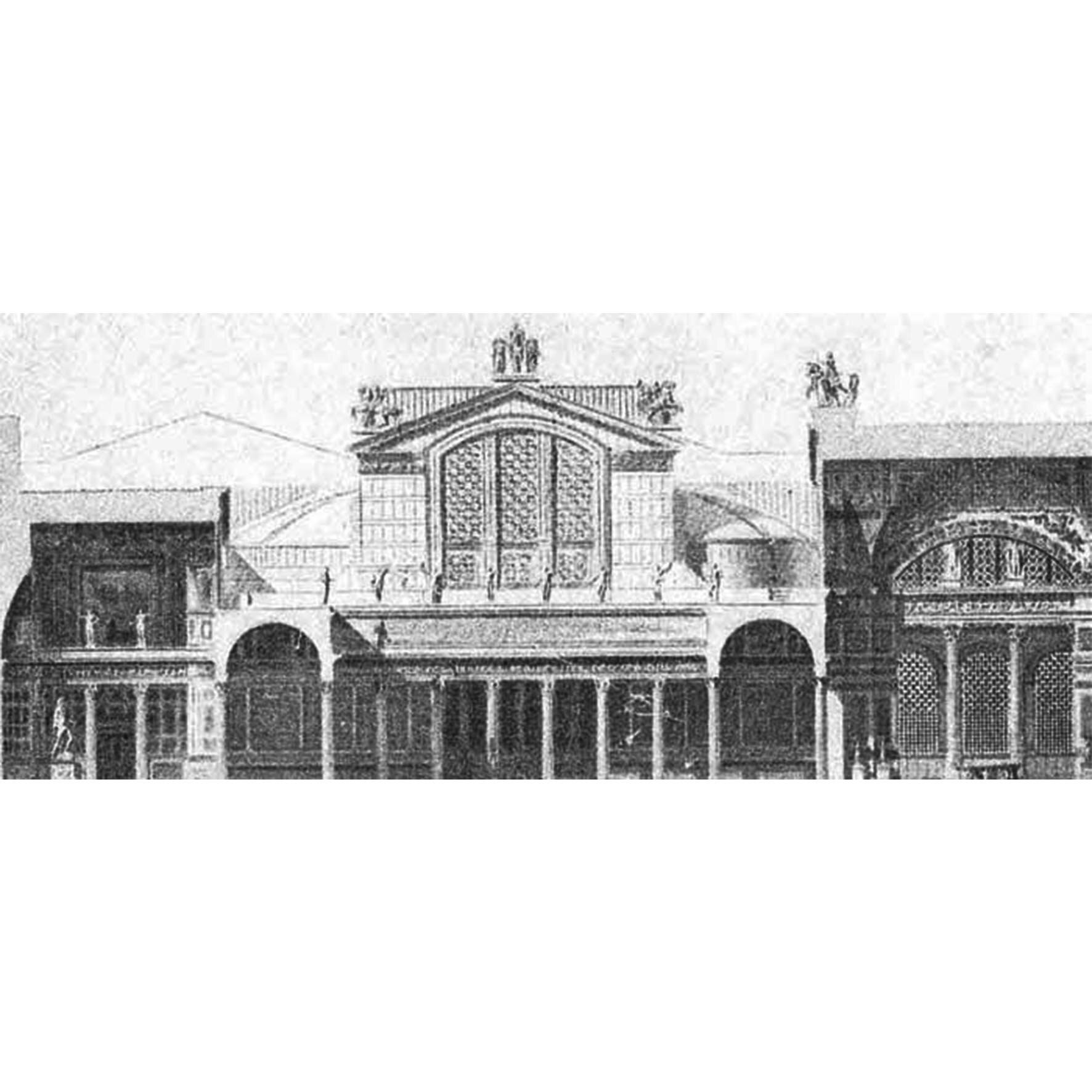

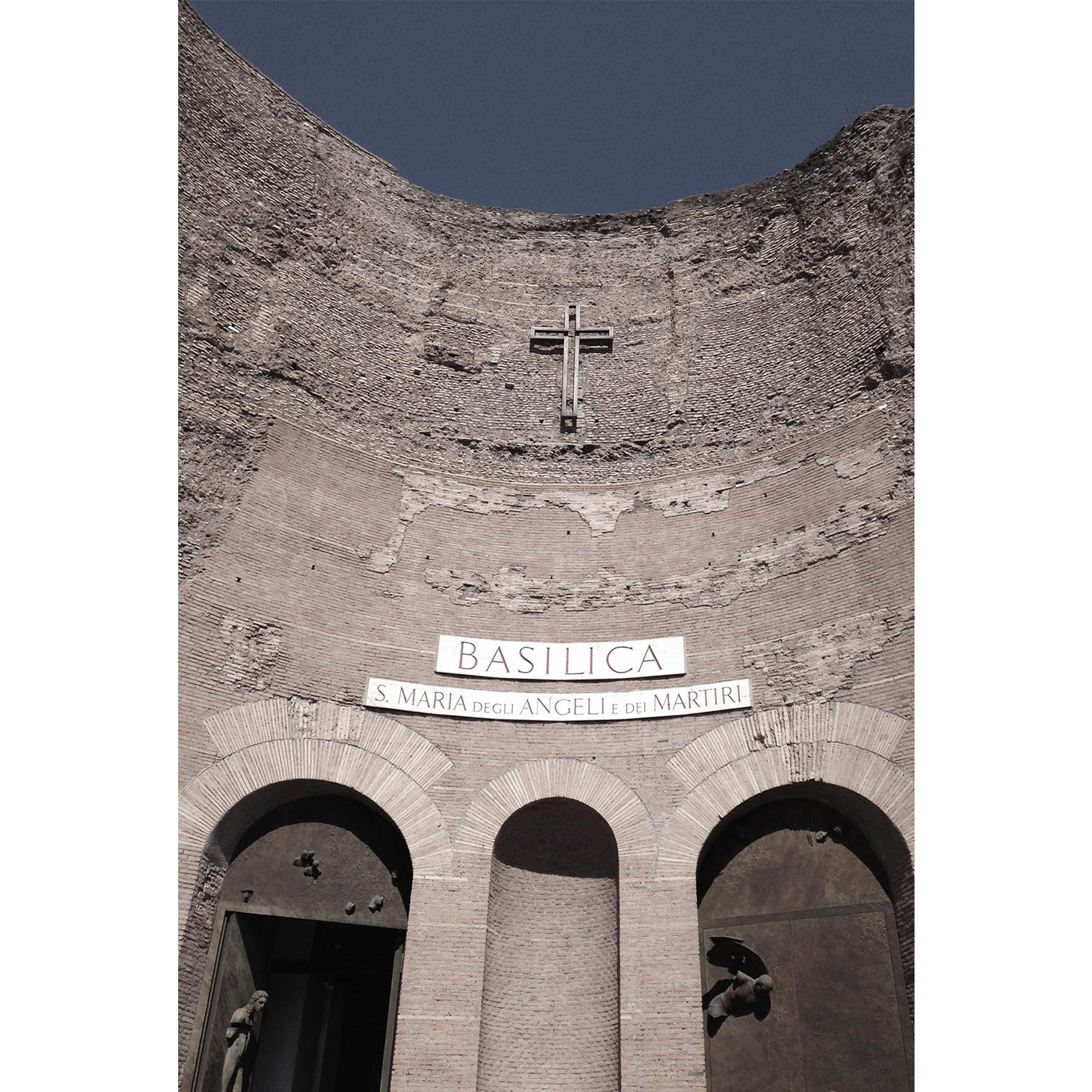

Aside from uniting one of Rome’s most typologically symbolic relics with one of the Renaissance’s most brilliant architectural designers, for me the church is more than the sum of its (extraordinary) parts. It exemplifies well the way apparent limitations of an existing structure can seed innovative solutions and surprising variations to well established archetypes (see my earlier blog on this subject here). In this instance, the existing proportions of the baths’ central hall created a transverse nave, significantly wider than its depth, resulting in a remarkable expanse of space beyond the proportionally constrained domed ante-chamber, and giving the chapels at each end a much more dramatic perspective. Heightening this sense of discovery is the omission of any ornament or ceremony to the façade (a subsequent change); instead the nave is entered through the craggy apsidal remnants of the former caldarium, creating an austere contrast to the scale of space and sumptuousness of decoration within.

Over a century after Alberti began the analysis and celebration of surviving Roman architectural relics, one can see how the glorification of classical ruins may have evolved into a reverence bordering on spiritual. Capitalising on the authentic purity' of the ancient baths to create a sacred space of divine worship remains in my view a masterpiece of ‘creative reuse’.

Charlie

images from the wonderful online archive at www.santamariadegliangeliroma.it