Who thought we'd only need 12 weeks for this much reflection, reaction and reinvention?

We at CWa have been so very lucky: loved ones, friends, associates and team members remain relatively safe and well, and we are so grateful for it. Like many I'm sure, lockdown has seen me looking longingly out of the window: Admiring the weather, waving to neighbours, enjoying an explosion of summertime flora and fauna, with clean air, quiet roads and empty skies. It's been a time of daydreaming. Of thinking what could be.

Three things struck me during this time:

- As an avid monitor of our national grid, our energy needs dipped only slightly these past weeks- even with such dramatic changes in lifestyle. This is quite significant: If we are to meet commitments to dramatic reduction in CO2 outputs, we need to keep thinking at a national scale: Something only possible at the level of central government.

- But we are making incredible inroads. At the time of writing, we haven't burnt any coal on the grid for nearly two months- and I remember getting excited by the record of 24 hours only a few years ago! To put this in context, we have burnt coal continually since the industrial revolution. We broke our record for wind generation this January (17129MW), and solar PV generation this April (9680MW). These are exciting steps, on a long journey- but absolutely in the right direction.

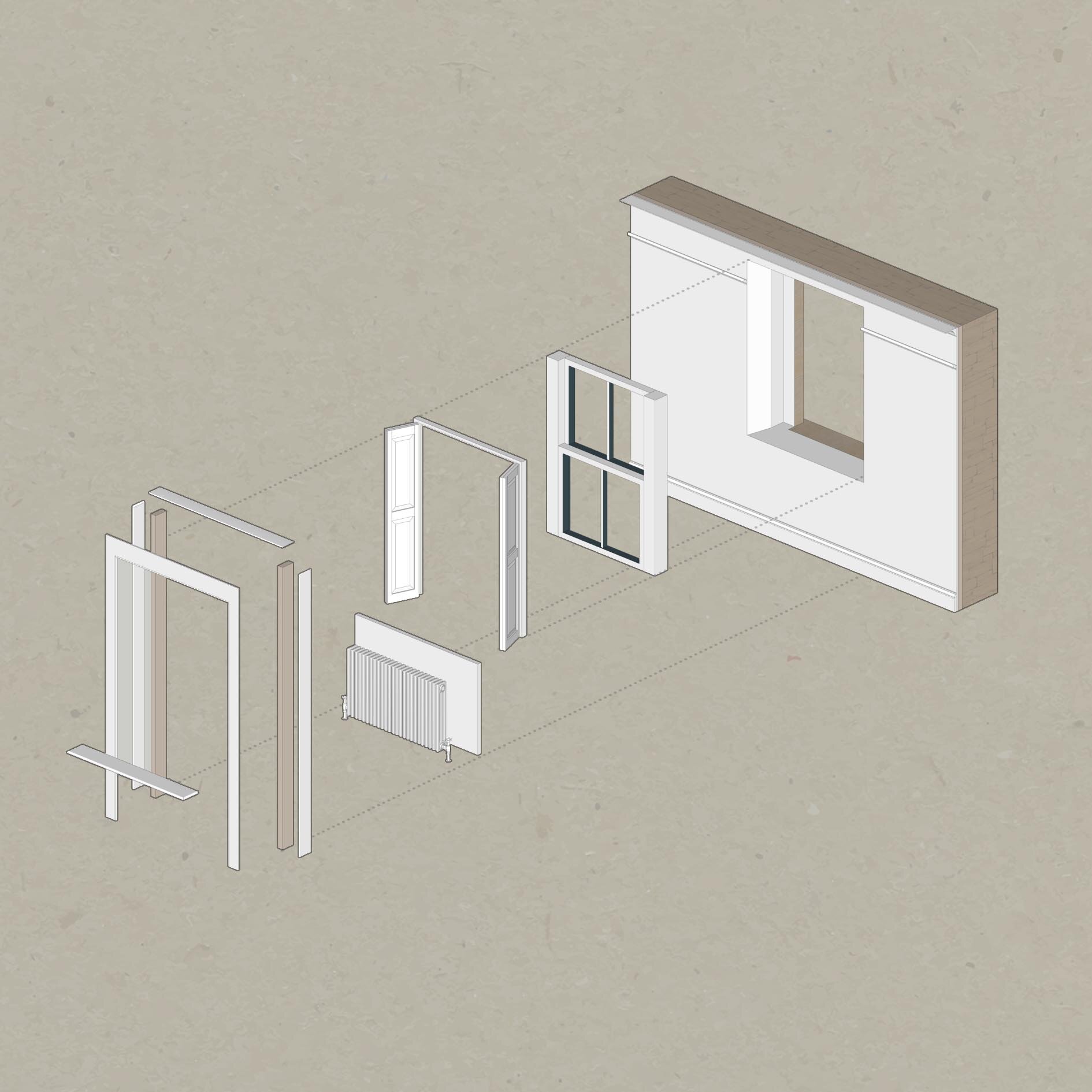

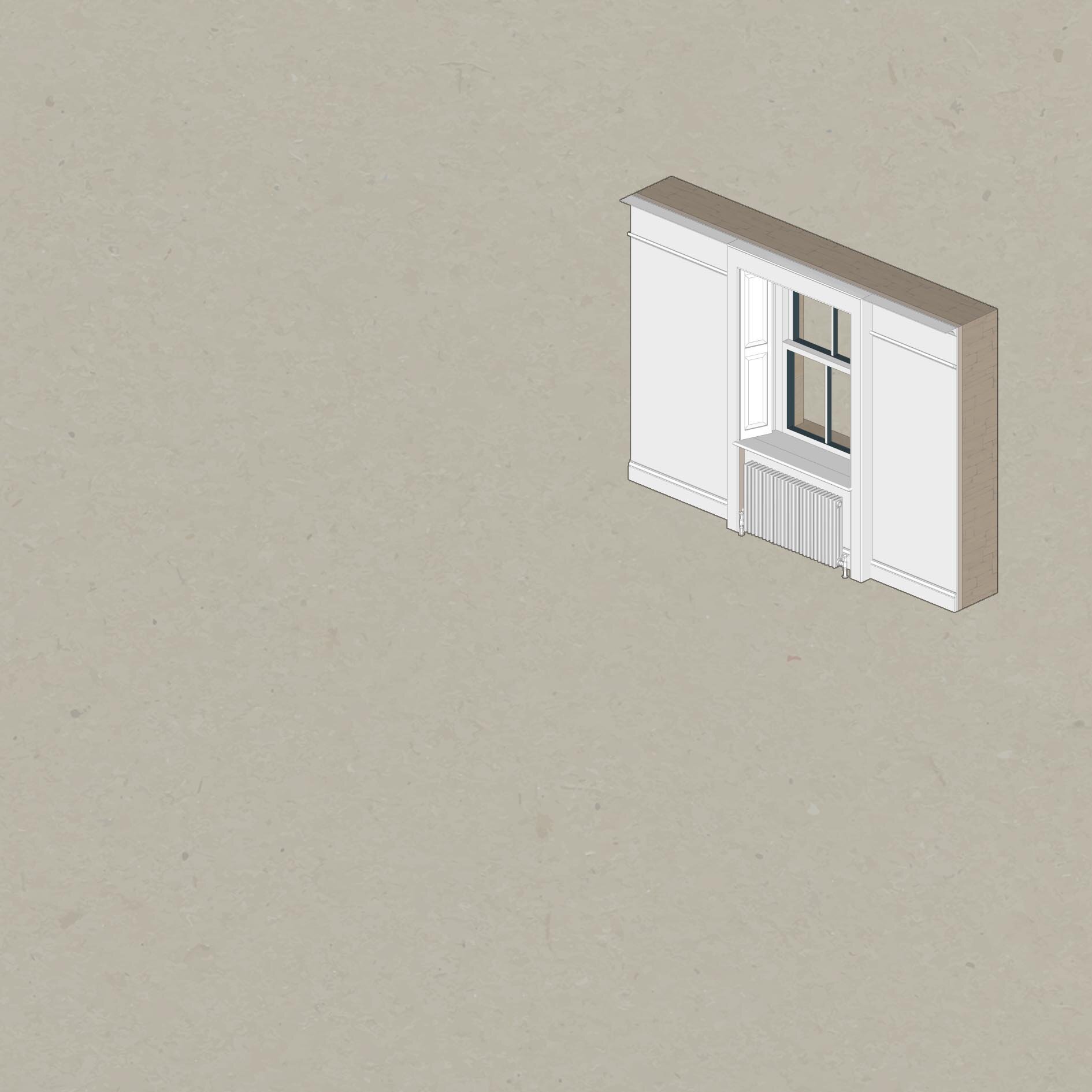

- This brings me back to my window. Alongside generation, we need to think about efficiency, and we need to think about our existing building stock. A key point of weakness in the thermal efficiency of any building will be their windows (especially so in a solid masonry building with leaky, single glazed, sash windows). I tried to think about all the things I could do to improve the efficiency in and around my window at home.