‘Let us condemn the heresy of workspaces in churches’ https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/jan/23/heresy-workspaces-churches-trendy-pod

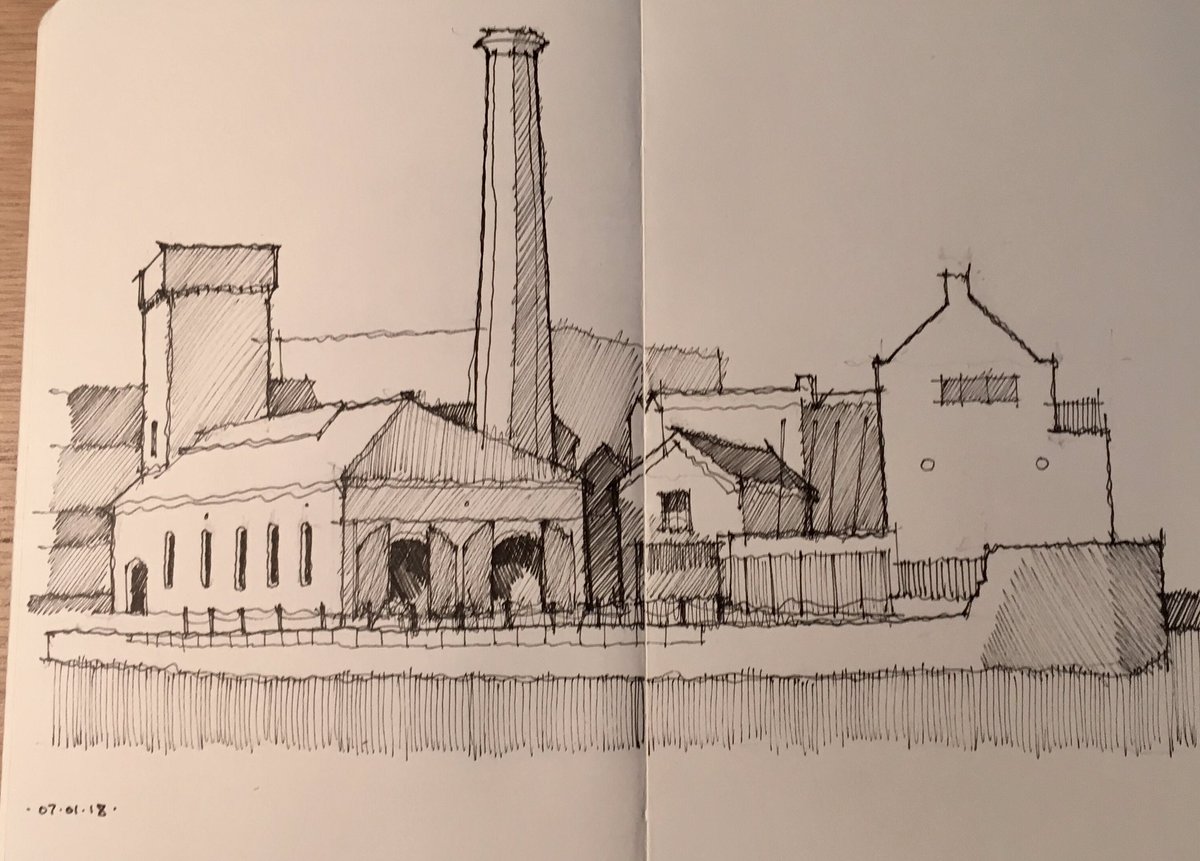

I was slightly disheartened to read the above comment piece criticising churches for broadening their appeal to both religious and secular communities, and it compelled me to defend the case for welcoming new uses into these ancient public buildings. Although the thrust of the article was directed against the potentially unhealthy changes to work patterns of millennial office users, it hinted at a disconcerting lack of awareness regarding the scale of the challenge currently faced by the UK’s churches, clergy and parishioners - even in wealthy and densely populated areas.

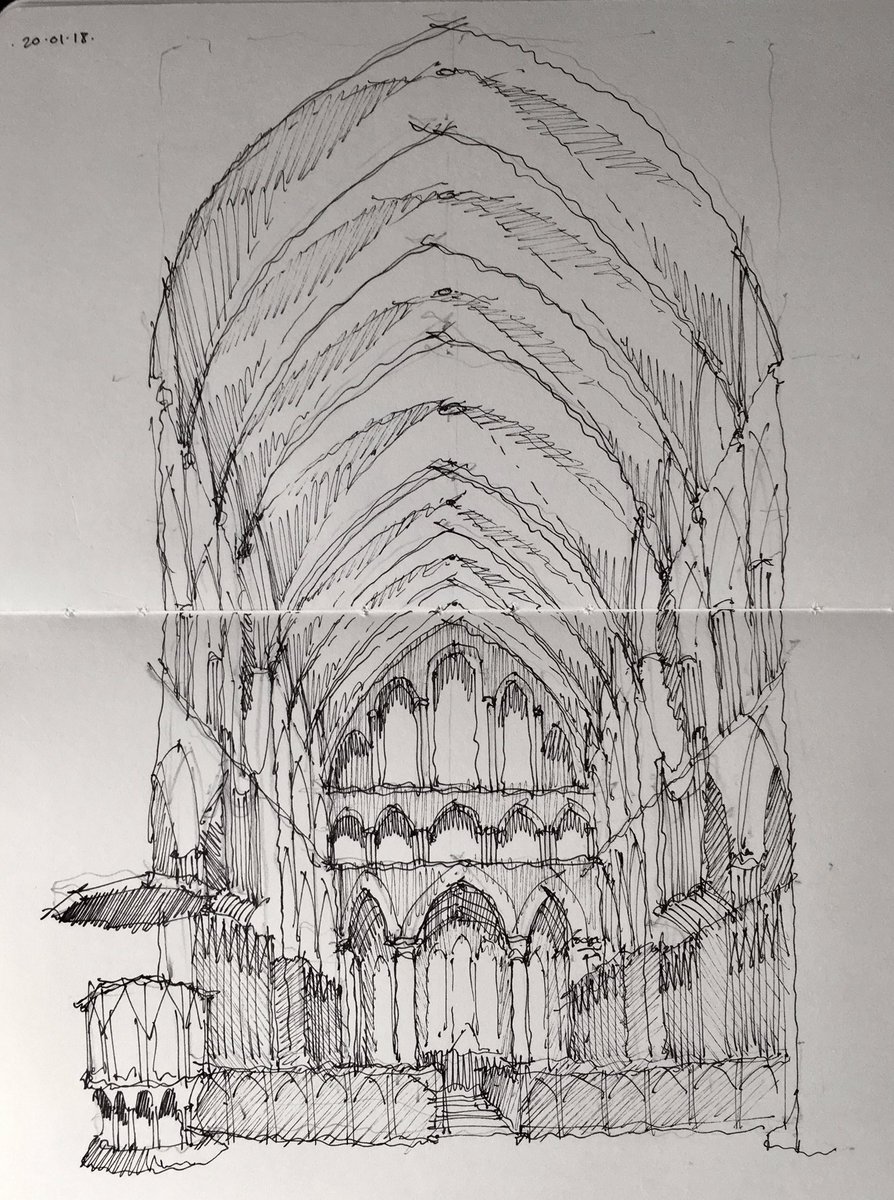

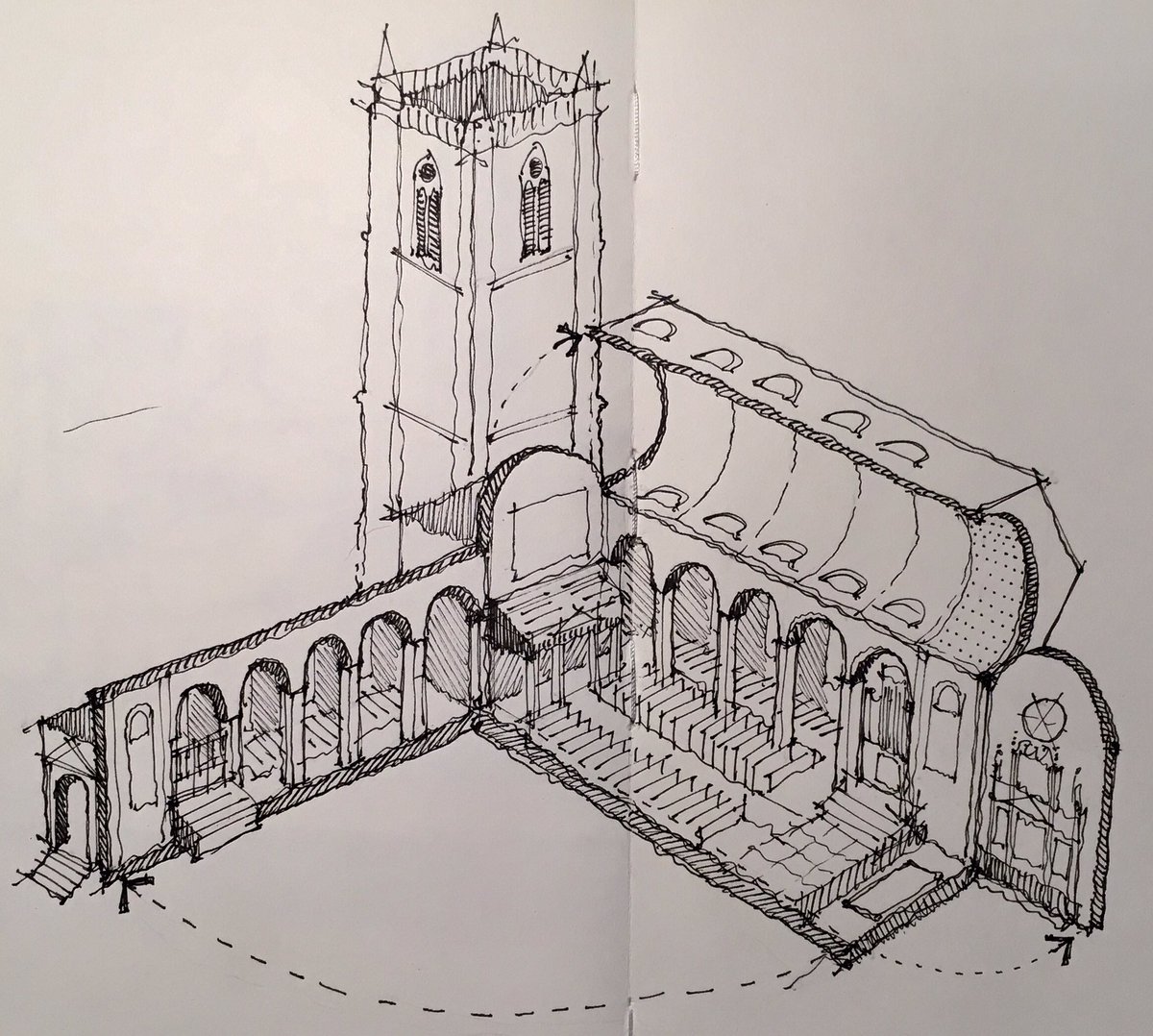

Although many commentators usually concede that new uses in under-utilised church spaces are a positive thing, they are often hugely restrictive as to what they feel appropriate or compatible uses might be. Many people love the romantic notion of solemn and quiet church interiors (in other words empty of people and activity), but rarely witness the daily life of the congregations that worship their regularly, and the necessary vitality that they require to survive.

Creating a welcoming environment for as many demographics as possible to use these amazing spaces (and if I were to be blunt – to generate revenue from them) is essential if we want future generations to enjoy them the way that we do – even if that is only culturally, rather than religiously. The suggestion that this sensitively managed evolution might be ‘heresy’ is clearly a provocation, but closer to the truth of some opinions than perhaps the author realises.

I might also add to this the social benefits of placing a church’s outreach right in the middle of a mixture of everyday and commercial uses, which helps to reduce the stigma and increase the visibility of facilities such as food banks and homeless support. The vibrant cohabitation of the crypt café and night shelters at St.Martin in the Fields is a great example of this.