There is a growing appreciation within the UK construction industry that the only realistic way of achieving our collective obligations to reduce carbon emissions, is by retaining and adapting our existing building stock – a position that Connolly Wellingham have been championing since inception, and a primary driver for our establishment of the practice. This necessary change will require a considerable attitude shift from the ‘business as usual’ approach of demolition and reconstruction that has been endemic to urban development across the UK, and nowhere more enthusiastically than in the capital.

The proposed application to demolish the historic Marks and Spencer department store on Oxford Street has been the subject of considerable debate since it was lodged in 2023. The applicant’s assertion that the aging structure is no longer fit for purpose as a retail venue and must be demolished and rebuilt from scratch has been challenged by a burgeoning movement of pro-retrofit campaigners, including Save Britain’s Heritage and the Architects’ Journal.

To further stimulate debate SBH and the AJ launched ‘ReStore’; a national competition for architectural concepts on how the M&S on Oxford street might be saved and reimagined – both as a specific proposal for the future of the department store and its West End context, and as a speculation on the future of the UK’s high streets more broadly, and how we might approach their aging building stock as an opportunity rather than a liability. Given CWa’s commitment to this cause, and a portfolio of work across the last 6 years through which we have developed and refined our architectural and intellectual position on this subject, we felt duty-bound to make a submission and to join this national debate.

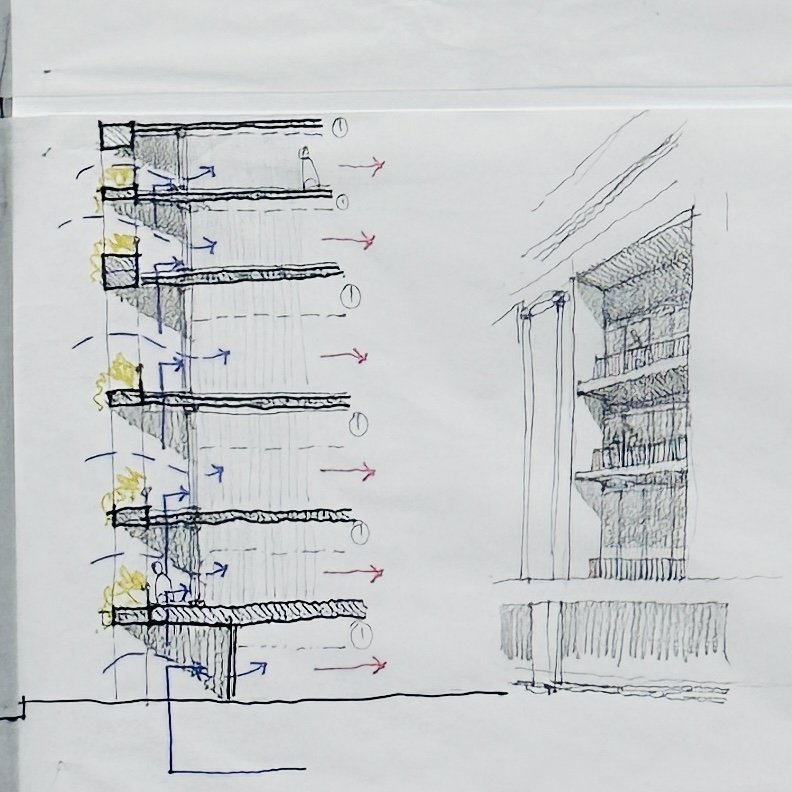

CWa’s submission was entitled ‘ReStore: Human scales’, and comprised of a deceptively simplistic single image that summarised a complex web of inter-weaving concepts. By illustrating a single structural ‘cut’, in the form of a cylindrical exterior lightwell bored through the existing concrete structure from basement to roof, the image begins to explore the following themes: natural light, passive ventilation, human scale, density, flexibility, historic street patterns, mixtures of complementary uses, the incremental loss of London’s public realm, the richness of architectural accretion, the clarity of architectural editing, and a future where bombast and grandiosity could yield to sensitivity and nuance. We were delighted to learn that our submission had been long-listed, and that we would have the opportunity to expand on our ideas at an interview with the judging panel.

In preparation for the interview we purposefully chose not to further develop the design of a possible proposal for the site, rather to draw together a breadth of historic and contemporary precedents through which we could expand upon our identified themes. These included Giambattista Nolli’s 18th century map of Rome, famously illustrating the interior of the city’s churches as public spaces of communal ownership, and Walter Benjamin’s critical analysis of the 19th century arcades of Paris, as a cultural and spatial revolution incited by the marriage of consumerism and urbanism. Finally James Stirling’s Number One Poultry, with its central atrium and iconic worm’s eye representation that had so inspired our initial submission – the perfect means to describe the complexity and generosity of London’s tall buildings from the humble perspective of the city’s public realm.

Viewed through this lens a newly carved atrium (singular or plural) could return a public right of way through the centre of the site, breaking down amalgamated mega-blocks to more closely resemble the pattern of their historic predecessors, with the new building envelope required to separate the interior from the exterior a new evolution of London’s street facades.

Imagining this intervention linked to others of its nature on at a city-wide scale, a masterplan emerges weaving a new city-scape through, in and under the London we currently know it. Like Wren’s plan to rebuild the city after the Great Fire, the need to reuse and modify our existing building stock is a challenge in response to an emergency situation, and one that must be executed on a city-wide scale. Whereas Wren’s plan remained unrealised due to a swift and staunch return to the city’s medieval street pattern in the weeks after the fire – this same will and pragmatism to maintain and work with an existing condition could be the reason that a vision like ‘ReStore: Human Scale’ succeeds.

Following our interview we were delighted to be invited as one of finalists to attend the live Charette event – a one day workshop for the six selected teams to develop their concepts and present them to the judging panel in person. One of the main elements that set our work apart from other teams was our decision not to identify a fixed new brief for the building, a position which was questioned by the judging panel. Instead we chose to spend the workshop refining and articulating our ‘long life, loose fit’ ideology in more detail, and in the context of this site, on this street, in this city.

When approaching interventions in a historic building we do so with the expectation that the building will out-live the brief we are asking to accommodate today – and that the best thing we can do to ensure a building is reused in future is by equipping it with a beautiful, flexible and pragmatic, sequence of spaces of varying size and character. In this way the ground floor of the structure might be as open and permeable as possible – even seceding to the public realm, in the spirit of Nash’s ‘Collective Colonnade’. The lower floors remain largely open plan, public uses just off the street that are welcoming, accessible and easy to navigate. Above these spaces become more compartmentalised; clusters of smaller rooms around cores of circulation and services – tenanted offices, flexible workstations, public facing service providers. The final upper floors become more cellular still; new residential homes of mixed size and typology, built lightly in timber and arranged in a new roof garden of private but shared outdoor amenity overlooking the rooftops of the West End.

Timber construction features heavily, as a way to quickly and efficiently intervene within the structurally massive existing concrete frame, but also reintroducing a human, makerly, quality that speaks to how we must build in the 21st Century. The interventions minimise embodied carbon, and seek a friend in the atria of nearby Liberty’s of London. Sustainable, natural materials are brought together in a way that is technologically advanced, more humane, and aspires to a renewed ‘state of the art’.

At the end of the session we were asked by the AJ to summarise our experience in 3 words:

Energetic. The 6 teams who were invited to participate grasped the challenge with a clear passion for the scale of the challenge - both on the site in Oxford Street, and as a global response to climate emergency. The breadth of ideas and approaches were impressive, and we felt really privileged to be counted among them.

Timely. The application to demolish the existing M&S building and the subsequent debate surrounding the case demonstrates that the tide is turning, and 'scrap and rebuild' resource intensive models can no longer be a standard starting point to development. As a practice established with a commitment to reuse-first design, it's exciting for us to see prevailing attitudes being challenged and momentum building.

Hopeful. The charette demonstrated that the expertise already exists amongst UK architects to progress this agenda - to create delightful and practical spaces within and on top of our existing building stock. Adaptive reuse is an opportunity and not a limitation. The sector is ready and is lobbying for the governmental and legislative oversight that is required to make meaningful change.

Although this is ‘paper architecture’, it has been really useful exercise for our young studio to collaborate on, and to help us collectively articulate how significant an opportunity the challenge of reuse could be – not just on a building by building basis, but as a chance to resolve much larger urban challenges; connectivity, accessibility, and occupation of public space. We want to thank the AJ and Save Britain’s Heritage for their generous hosting of this event and for giving CWa the chance to participate. Along with our peers in the industry, we continue to watch the live debate surrounding the Oxford Street site unfold with much interest.

Follow the below link to read Olly Wainwright’s review of the Charette for Guardian Culture:

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/article/2024/jun/07/marks-and-spencer-flagship-store-london-art-deco